Elon Musk owns Twitter; politicians should leave

Analysis of 460,501 tweets from U.K. MPs suggests that posting on social media is not very useful for politicos.

Dear readers,

As I write this episode, Elon Musk just spent $44 billion to buy Twitter; this episode was about British politics until Friday the 28th; now it is about Twitter, its effect on the public sphere, and the politicians, journalists, actors of the public sphere that, maybe, should get the hell out of social media and go out more, as an old FT column said back in 2016.

On the technical side, I am going super experimental with my first attempt at data sonification, the art of translating data into music. TwoTone provided the software. Data about polls come from the fantastic dataset Europe Elects – buy them a coffee if you can.

Thanks for reading.

BRUSSELS – What did Elon Musk buy for $44 billion? A thriving platform or an almost useless vacuum chamber? Twitter was one of the core pillars of Web 2.0, but after some years, users began complaining about the micro-blogging platform. The Trump presidency, the anti-vax movements, and Russian propaganda conjured against what was once seen as a system infrastructure since 2016. Consequently, Twitter no longer looks systematically important, and data from the British political Twittersphere seem to confirm this hypothesis.

**Keep up with market and investment news in just 3 minutes a day.

InvestorSnippets is a free daily newsletter with bite-sized news on markets, stocks, and ETFs. They are all curated and snippets with links to the full story. It’s not a commentary or an analysis, just something short and simple to keep you quickly informed!**

To understand if Twitter is relevant to public opinion, DaNumbers tried to measure if the sentiment of tweets can predict public opinion polls. Data from more than 400,000 tweets by British MPs suggest that the public pays little attention to what happens on the platform. In contrast, the developments within institutions drive public opinion more than anything else. The following audio will help explain this point.

This is the first example of sonification in this newsletter. It is a 15-minutes long track, but readers do not have to listen to all of it. The arpeggio from the piano represents the trend lines of the polls as collected by Europe Elects for the Labour Party. The pizzicato bass line is the level of populism in the Labour MPs’ tweets. The two lines were put on minor third apart.

The frequent dissonances outline that the sounds rarely follow the same trends. Populism grows and declines entirely differently from the variable it tries to predict. Readers can control the speed of the audio with the controller on the far-left side of the player. Still, even if readers skip some part of the track (the track plays data from January 1, 2020, to October 12, 2022), they will come to the same conclusion: sentiment does not affect public opinion polls. Please note that Populism and other sentiment values are 20-day rolling averages and that polls are smoothed with a bicubic spline.

The spike in the sounds at the end of the track seems to contradict these conclusions, but the relationship at 15 minutes sounds more casual than actual. How did DaNumbers get there? Performing a sentiment analysis and trying to make sense of the data using some statistical techniques.

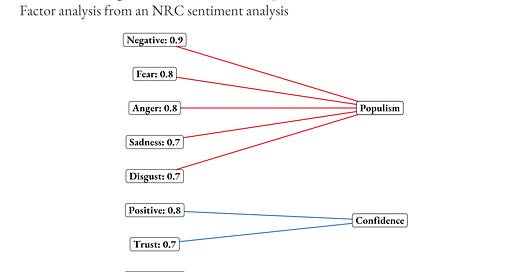

The algorithm used for this newsletter is the NRC. This algorithm is a well-known tool for exploring a complex array of sentiments. It works like a crystal prism for light: it takes a word and gives it a score (an integer number) over ten dimensions; the sum of these numbers allows one to figure out the vibes of a text. The dictionary of this method is open-source, and it is available here. DaNumbers – as it did one year ago – decided not to stop there: thanks to factor analysis, it collected three dimensions of sentiment: Populism, Confidence, and Expectation. The following chart will explain better.

Factor analysis, by handbooks, is a statistical technique that tries to understand what one or more latent variables could look like. More simply, factor analysis is what motorists do when they see a dent in their car’s bodywork: they know the shape of the dent (in this case, the raw sentiment values), and they try to imagine the shape of the object that caused that dent.

In the above chart, we can see how generically negative sentiments aggregate together. Factor analysis does not give names to the variables it generates; they are arbitrary even if the chart explains them relatively well: an essential element of Populism is that it rides the discontent of the people against the political élite in an angry and, perhaps, not so proactive and discouraged fashion.

Similar reasoning goes for the other two dimensions, with Confidence that is just a synonym for trust, whereas Expectation pools positive sentiments with an outlook for the future given by anticipation. If these sentiments had to be weaponised in political communication, how would British MPs use them? The following chart answers.

The chart collects the sentiment tweets by current MPs. The chart displays the 20-day average of the different sentiments to provide better visualisation and reduce noise. The chart covers all parties but focuses on Tories and Labour. The horizontal axis starts from 2016; the right-hand limit is October 12, 2022.

During the electoral campaign that saw Boris Johnson achieve a landslide in 2019, Labour appears to have lost confidence. The clear marks of the aggressive Jeremy Corbyn campaign can be seen in the Expectation and Populism sides. The chart displays interesting spikes for the Labour, whereas the Conservative parties kept a relatively low key.

DaNumbers had identified some of these patterns already last year. The absolute novelty in this context is that the Conservative Party keeps a consistent language. In all three dimensions and over time. In contrast, Labour, during the controversial Jeremy Corbyn leadership, pushed firmly toward a more populist stand. Despite the recent drama, the language of the Conservatives remained constant, trying to display a calm, relatively confident party that knows what it is doing.

The Keir Starmer leadership brought a more consistent pattern on the opposition side. Labour needs to use populistic rhetoric; after all, it is a leftist party that should care about the working class. Despite some commentators arguing that Mr Starmer “Sounds like a Prime Minister,” there is a general lack of confidence that the Labour, in general, might still be their weak spot in their communications, provided that Rishi Sunak consolidates his leadership.

It is interesting to compare the new Prime Minister with the opposition leader. The two men – it is fascinating to note that a woman does not lead the Labour, whereas the Conservatives already put three women on the dispatch box – do not tweet that differently, and this is maybe part of the reason behind Keir Starmer’s credibility, as the following chart helps explain.

Here, the big dots represent the average tweet by the two men. The points scattered all over the horizontal axis are single tweets. We see from the chart that the two leaders look closer than their parties despite some exceptions on the far-right end of the chart. The very different part is that Keir Stramer appears to have stronger rhetoric. The black error lines under the big average dots indicate that, despite exceptions, the PM and the opposition leader maintain a different tone of voice. Which of the two speaks like a Prime Minister? It is hard to say. For sure, Mr Stramer sounds more confident than Mr Sunak.

The problem with sentiment analysis-based stories is that they do not adequately grasp the subject of the texts they analyse. In the past, DaNumbers used a Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) to spot topics in the abstract of more than one million New York Times articles. The result was gibberish when it tried to do the same in this context.

LDA algorithms allow users to choose the number of topics they want to find according to word frequencies: the more words stick together, the more likely they deal with the same topic. Here, the LDA could not spot coherent arguments with words like “consistent” popping all over the place. Although this is a well-known problem within Twitter analyses, its ramifications help explain why Twitter is becoming less and less relevant.

Being a place for short statuses, tweets need to lack plenty of information, assuming readers are aware of their context. This is why it is perhaps hard to find a sense in tweets – despite a 400,000-strong corpus. Although the subject is essentially one: public affairs, this cacophony of tiny status updates is likely the reason behind the demise of Twitter as a place of influence. Two more charts elaborate on that.

Here we see a series of scatterplots divided by party and sentiment. The points are the values of the 20-day average of view combined with the respective value of polls. Polls are not run every day, so the values displayed here are a smoothed version of them. Smoothing is necessary because votes are not all the same, and they give slightly different results; to make sense of them, poll aggregators interpret them using a bicubic spline that makes trends more evident. Data are from Jan. 1, 2020, to Oct. 12, 2022.

We see here that there are two different trends for the Conservatives and the Labour party. Labour populistic tweets are positively related to higher scores in the polls. Data for the Conservative party are fuzzier. On the one hand, it looks like less confident tweets yield worse polling results, for example. The problem is that there is little evidence that sentiment and polls are related. Performing a linear regression not considering parties, the p-value is above 0.90, meaning that the model is meaningless. The explanation of the chart, then, is more complicated.

Superficially, the chart could be an iteration of Simpson’s paradox – a paradox where two variables display different signs in the correlation when they are divided into groups. Less superficially, does it offer a glimpse into how public opinion at large and the Twittersphere interact with each other?

The idea that Populism and polls go together here looks evident. On the audio at the beginning of the story, a bit less. The answer could come from an obscure chart, the second of this section. Here DaNumbers tries to get to the bottom of the issue by reasoning in terms of difference rather than absolute values.

The Europe Elects dataset delivers the date of the fieldwork of polls. To get a representative sample, operators need to phone random call people. If pollsters use the Computer Assisted Telephone Interview, they could call randomly generated phone numbers and ask the questions one by one: it takes time. In the dataset, the average time between the fieldwork's beginning and the end is 1.7 days. Rounding, it means two days.

Comparing the 2-day differences in sentiment and poll results, we see the points gathering around the origin of the x and y-axes. That means that there is no relationship whatsoever between these two variables. The theory behind this plot is that whatever happens in social media during the data collection phase of the polls affects the result of the polls. The chart above blatantly disproves this assumption.

A final objection could argue that it is never a good idea to regress between two smoothed values across so much time. Maybe it is correct, and perhaps this objection requires some further research. Yet, the charts seem to fit with the story's bottom line: after 15 years of Twitter frenzy, the (at least) British public sphere is ready to move on.

Elon Musk, apparently, bought a very pricey vacuum chamber. One suggestive hypothesis is that social media represents the vacuum politics rule from. This was the subject of a modern classic of political science: Ruling the Void, by Peter Mair. In that book, the Irish political scientist argued that democratic leaders rule from the ivory towers of their institutions without any contact with what was going on the ground.

This also applies to political communication. It is easier to write a tweet than face an angry constituent. In fact, the ruling class chose the easier wrong instead of the harder right. Will the new Twitter ownership force politicians to go out more? Western democracy certainly hopes so.

Click here for the code used in this newsletter.

See you on the Spatial metaverse Tuesday, November 1, at 9 p.m., Brussels time.

A great article with excellent knowledge. It was a pleasure to read your article

if u want to read on VR Industry you can visit this site :- https://www.vyugmetaverse.com

I’ve said this from the off they categorically should be no where near it.