How The New York Times changed after September 11

An analysis of 1,574,957 articles investigates changes in the NYT's evolution between September 2001 and December 2020

Dear reader(s),

Twenty years ago, an Italian teenager fell in love with journalism. When I saw the coverage of September 11, I immediately found out what I wanted to do in life. This special issue of DaNumbers is an hommage to the job I love in the way I like doing it: with data.

MASSA MARITTIMA, Italy — When people said that after September 11 ‘nothing would have been like before,’ they weren’t thinking about the evolution of journalism. Yet, the terror attacks against New York and Washington had broad ramifications in the news industry too. So far, none has measured what newspapers did in the last 20 years. Here, DaNumbers studied one of the powerhouses of journalistic innovation: The New York Times.

Recently, the New York-based newspaper published an API that allows users to access information about published articles. DaNumbers downloaded metadata for 1,574,975 articles published between September 1, 2001, and December 31, 2020. The question was: how did The New York times adapt to the digital world?

The crucial turning point in the paper’s history was the introduction of a paywall. In 2011, the newspaper decided to allow access to its articles to subscribers only. This innovation allowed the NYT to stop bleeding cash, fix its balance sheet, and consolidate its position on top of the news industry.

Adapting to the new world

When newspapers adopt a paywall, they get into a new dimension. A free newspaper is a content factory that needs to produce many articles to keep the pageviews high. They need those pageviews because ads, in the digital environment, are cheap. Newspapers based upon subscribers can afford to do things differently, as the following chart shows.

The blue area is a line representing the daily mean of words per article. The grey area around the blue one is the standard deviation of the mean. The standard deviation, in this case, represents where news stories which are not within the average are more likely to be. The red line is a statistical smoother that allows getting an overall trend about the data.

Here we see what the business model evolution meant for The New York Times: the paywall led to longer articles. According to the red trend line, articles published daily are now around 1,000 words long. In 2001 they were almost 25 percent shorter. Articles became longer until 2005. Their length grew again since 2008 and, as the subscription model became more consolidated, their length kept growing, reaching some stability only after the arrival of COVID.

The noise in the chart is because The New York Times' articles are not all the same. Also, the newspaper publishes news on a lot of different subjects. This variety makes the New York Times special. But the newspaper relies on a limited commodity: its workforce. Being journalists human, they need to produce less and to focus more. And the paywall allows them to do it, as the following chart shows.

The chart measures how many articles the newspaper published between September 2001 and December 2001. We can immediately see how the number of daily articles changes according to the days of the week. During the weekend newspapers publish fewer articles than they do during the week.

The chart shows something typical for the '00s, the deluge of digital content by newspapers. Such deluge stopped right before the newspaper introduced its paywall. Before the paywall, there had been days where the newspaper published more than 700 articles. Before 2010, there had been months where the NYT was issuing more than 500 stories per day. This is not by accident, given that it coincided with some institutional doping.

Back in the days, one of the fashionable things to do for a newspaper was to have a blog section, where journalists or writers could express themselves more or less freely. Blogs were innovative and cheap. They allowed having a lot of pages for ads without the need to organize the complex logistics of a story from some exotic part of the world. This course of action changed with the new business model which is based upon subscriptions.

Format, sections, multimedia

Multimedia content is something that we learned o use since September 11. With the developments of Flash, HTML5, etcetera, we now live in a media landscape where video, text, and images blend.

Multimedia journalism, though, does not grow on trees. This newsletter alone implied circa 740 lines of code only for data analysis and visualization. Twenty years ago, everything was more complicated. Blogs represented an inexpensive way to be modern without putting together technologies people didn't know. The following animation will shed more light on this aspect.

Here we see the number of monthly published articles by sections. The chart shows three things. First, The New York Times is a local newspaper. So many news articles about New York could have implications in its world views, as we will see. Second, the New York Times is not a newspaper that covers politics a lot: its focus is on international and domestic affairs.

The third thing is that blogs were crucial only in the second part of the '00s. Between 2006 and 2009, we see the number of blog posts published monthly grow up and decline. The Other section (an arbitrary aggregation of different sections other than DaNumbers explicitly wanted to consider) shows that The New York Times tries to be a one-stop-shop for those who want to know more about the world.

The data display blogs as a section but, more appropriately, they are a format. The New York Times API can give information on types of published articles. This information allowed DaNumbers to analyze the evolution of multimedia content over the years. If we imagine blogs and multimedia content as opposite journalistic philosophies, we see that none managed to win in The New York Times' newsroom, as the following chart will show.

In the chart, we see the daily share of multimedia articles over the years. Even though The New York Times is a powerhouse of innovation in journalism, multimedia content rarely represents more than 10 percent of published articles daily. The COVID pandemic demanded more multimedia content, but this type of article didn't manage to disrupt The New York Times and to become the new standard of news presentation.

This relative conservatism by The New York Times could be seen as a form of prudence towards technology on one hand or, on the other, as a sharp focus on what readers want. And this aspect can be found in the way the newspaper has covered world affairs since September 2001.

The world from New York

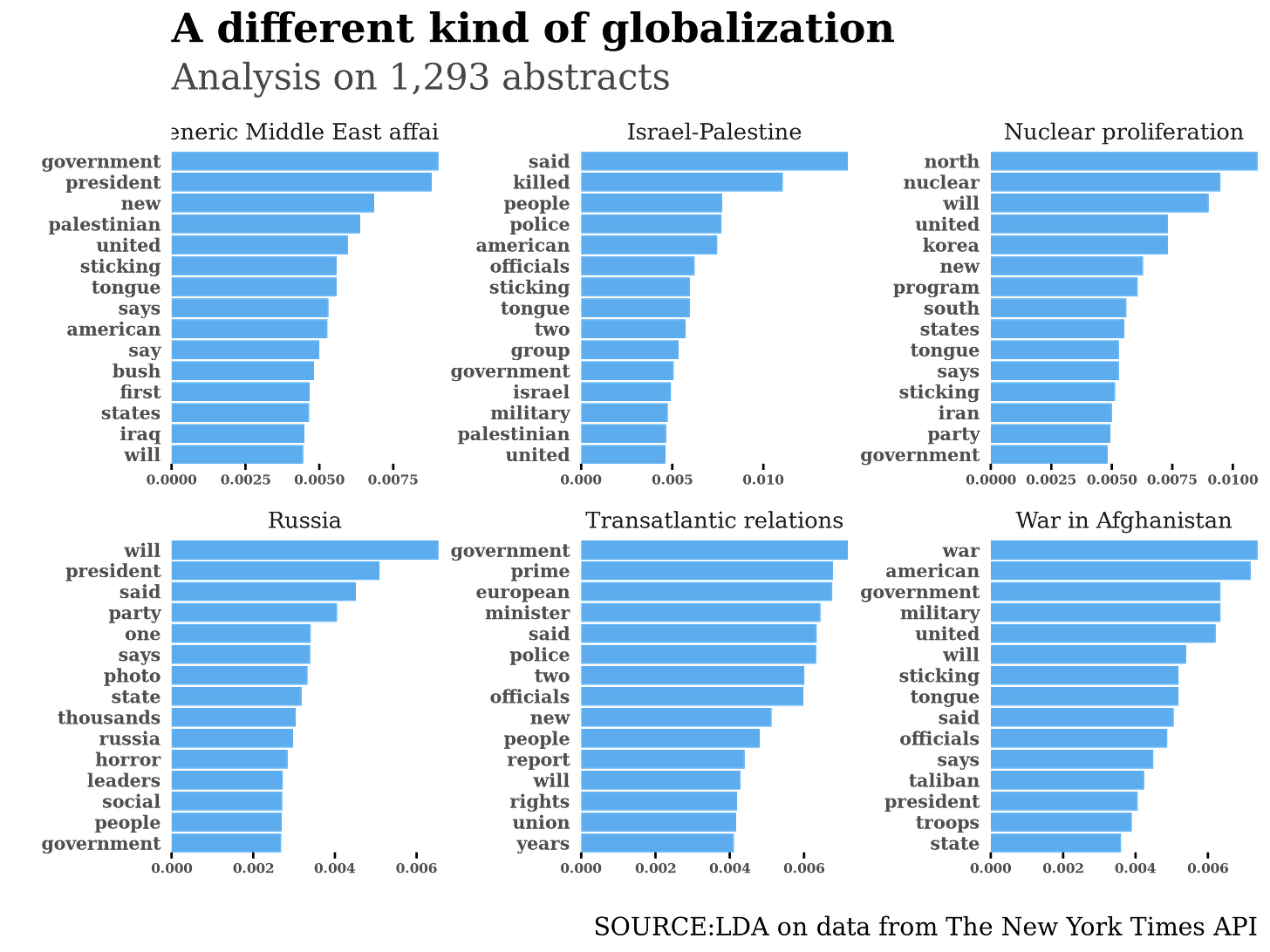

This section tries to take the World section of the New York times and, using an LDA algorithm, it tries to extract the topics of the foreign affairs coverage by the NY newspaper.

After this selection, DaNumbers sampled a quarter of the articles in the news dataset and used it to train a model. The model, then, was deployed on the rest of the dataset. Here is a chart about the classification of the training dataset.

According to his model, The New York Times' audience reads about an area of the world from Paris to Kabul. The topics identified are the War in Afghanistan, the nuclear programs of Iran and North Korea, the Middle East. Moreover, we have some coverage about transatlantic affairs, the middle east, and the Israelian-Palestinian conflict. This doesn't mean that the newspaper doesn't cover China, Africa, or South America, it only means that, on aggregate, the audience is still more interested in Eurocentric news rather than real global news.

In this case, geography matters: New York is on the East Coast so it is reasonable to think that the focus of the city is on the other side of the Atlantic rather than elsewhere. This is a constant for the last 20 years. The following chart offers more insight.

The chart shows how likely articles are to talk about a given subject. The way topics evolved for the last twenty years shows a constant interest in Europe, Russia, and the Middle east. Despite model limitations, the chart shows how, in the narrative, world affairs are all connected.

This network of dossiers is not exhaustive of world news, and readers know very well. Yet, The New York Times behaves with topics in the same way it does with formats: it knows what its readers care and it gives it to them, even if it may look like it is missing something. The problem is that that something might not be interesting for its subscribers.

Conclusions

After September 11, journalism changed too. The New York Times made a bold movie adopting the paywall ten years ago, but it didn't disrupt how it tells stories. Multimedia journalism became some of the most engaging content by the newspaper, but it didn't move the focus away from written news stories.

Also, in terms of coverage of world affairs, The New York Times didn't try to steer the debate showing under-reported events, focusing on well-established areas of interest in the world. Also, the U.S. fought two wars in the Middle East and Central Asia, keeping the spotlight on those areas.

The real change is the output of that massive machine which is The New York Times. Building upon its heritage, The New York Times built a digital newspaper that produces fewer articles than in the past. It might have less multimedia content than one would expect, but the focus on written stories is what allowed some of the most innovative journalistic products to be published.

Here is the code used for this issue.

Thanks for your attention, and see you soon.

Francesco

I really enjoy there number driven articles! Thank you so much for your kind words in our group today! I don't really get to talk to anyone about my writing because I would sound insane! Thank you for accepting me! Here is a link to my other page. I look forward to speaking with you in the future. I'm all over Chuck Palahniuk's comment section if you want to check that out as well. https://candice372.substack.com/p/uber-for-urns