Populism on Twitter might be a problem for the Labour Party

A comparative analysis of tweets by British MPs explores populism in U.K.'s Twittersphere

Dear readers,

Last month was very rewarding for DaNumnbers. First, this publication got featured by Substack.com, our host platform. Moreover, Datajournalism.com, the data journalism division of the European Journalism Center, deemed this newsletter as 'noteworthy' in one of their articles.

Speaking of Datajournalism.com, they just released a questionnaire about the status of data journalism (in Italian and English). Fill it now, and you might win a trip to next year's International Journalism Festival in Perugia, Italy.

As far as the contents of this newsletter are concerned, DaNumbers is going to Britain, where we try to understand more about how MPs tweeted recently. Have a nice read.

BRUSSELS, Belgium – Something happened after the Brexit referendum. Like most of the political systems all over Europe, Britain experienced a wave of populism. According to common sense, populism is a feature of the global Right. At the end of the day, Donald Trump, Boris Johnson, Matteo Salvini, and Viktor Orbán all fall within the definition of the populist leader. British MPs on Twitter seem to have tried to react to right-wing populism symmetrically. Recently, Laburist MPs followed rhetoric that can be deemed as populist. A chart might shed some light on this aspect.

Here, we see the evolution of populist rhetoric on Twitter by current British MPs. The chart shows the 20-days average of Populism on MPs Twitter profiles since 2010. We see that Twitter populism started to be a weapon on the left's hands after the 2017 general election. Back then, the Labour, led by Jeremy Corbyn, tried to gain the spotlight on social media, raising the tone of voice and starting a trend the new leadership was not strong enough to separate itself from.

The Labour party seems to have a very complicated relationship with Twitter. In practice, it looks like its MPs cannot achieve a consistent strategy that would allow them to catch voters' interest on social media without scaring them. On the other hand, the Conservatives look like they are not embracing Populism on Twitter, keeping a consistent tone of voice over time.

The analysis of the first chart might have some problems. It considers only MPs elected in the 2019 General Election by the current affiliation, and it does not consider tweets by UKIP, which is not currently represented in the Parliament. The data come from a sentiment analysis processed on more than 400,000 tweets. For technical reasons, DaNumbers decided to limit the number of collected tweets to the latest 800 for circa 580 Twitter profiles by MPs representing the overwhelming majority of sitting MPs.

The sentiment analysis carried is based upon the NRC algorithm. The NRC algorithm was developed by Canada's National Research Council, and it scores text under these dimensions: Anger, Anticipation, Disgust, Fear, Joy, Sadness, Surprise, Trust, Positive, and Negative. Using a factor analysis, DaNumbers reduced these ten dimensions to three: Populism, Confidence, and Expectation. The following chart will show the results with the details per tweet.

The chart above shows quite well why this populist evolution by the Labour passed largely unobserved: tweets pretty much look the same. An analysis of the average Populism by individual MPs will shed more light on this.

The above chart shows how MPs from the Labour tend to be more populist than their colleagues. LibDems are also relatively high on the Populism scale as well as some tory MPs. This chart might lead to believe that there is a divide between the parties, as far as Populism is concerned.

The hypothesis here is that leftist MPs can afford to use harsher rhetoric because they address a specific population group, possibly less affluent and educated than the Conservatives. However, this is hardly the case, as the following charts show.

The above chart represents the level of Populism in MPs by the share of outstanding students in their constituencies. The latter indicator is used as a proxy to assess the education level in a given constituency. If there had been a relation between the two variables, the points would have gathered around the diagonal dashed line. However, the random pattern of the points shows that such a relation does not exist. This trend looks the same for other parties, too, as the following scatterplot shows.

Here, on the horizontal axis, we have the level of readability of tweets. In this case, there is a minimal significant relation between readability and Populism. There is a slight trend by more populist MPs to be more readable when they are more populist. Yet, cases like Boris Johnson and the Speaker show another way to communicate on social media.

In particular, the Speaker can't be populist given their role in the House. But Boris Johnson is, on social media, less populist than his primary opponents. The leader of the LibDem, Ed Davey, is exceptionally high on the Populism scale, not far from SNP leader Ian Blackford. Keir Stramer, on the other hand, looks like the most readable frontbencher, at the right-hand limit of a crowded cloud around a Flesch level of 50.

The Flesch score is a readability index that uses the length of words and sentences as a reference. Being a fraction -- and some tweets very short --, some tweets can have negative values, which DaNumbers decided not to consider for this chart. A level of 50 means that the tweets require at least some secondary educations to be read. The subject of politics is intrinsically tricky; thus, this level is perhaps in line with expectations.

The last chart suggests that the main British parties do not talk to different people when they campaign on Twitter. Although data on the demographics about the two sides are not present, it is clear that they are competing for attention within the same social strata, at least on Twitter.

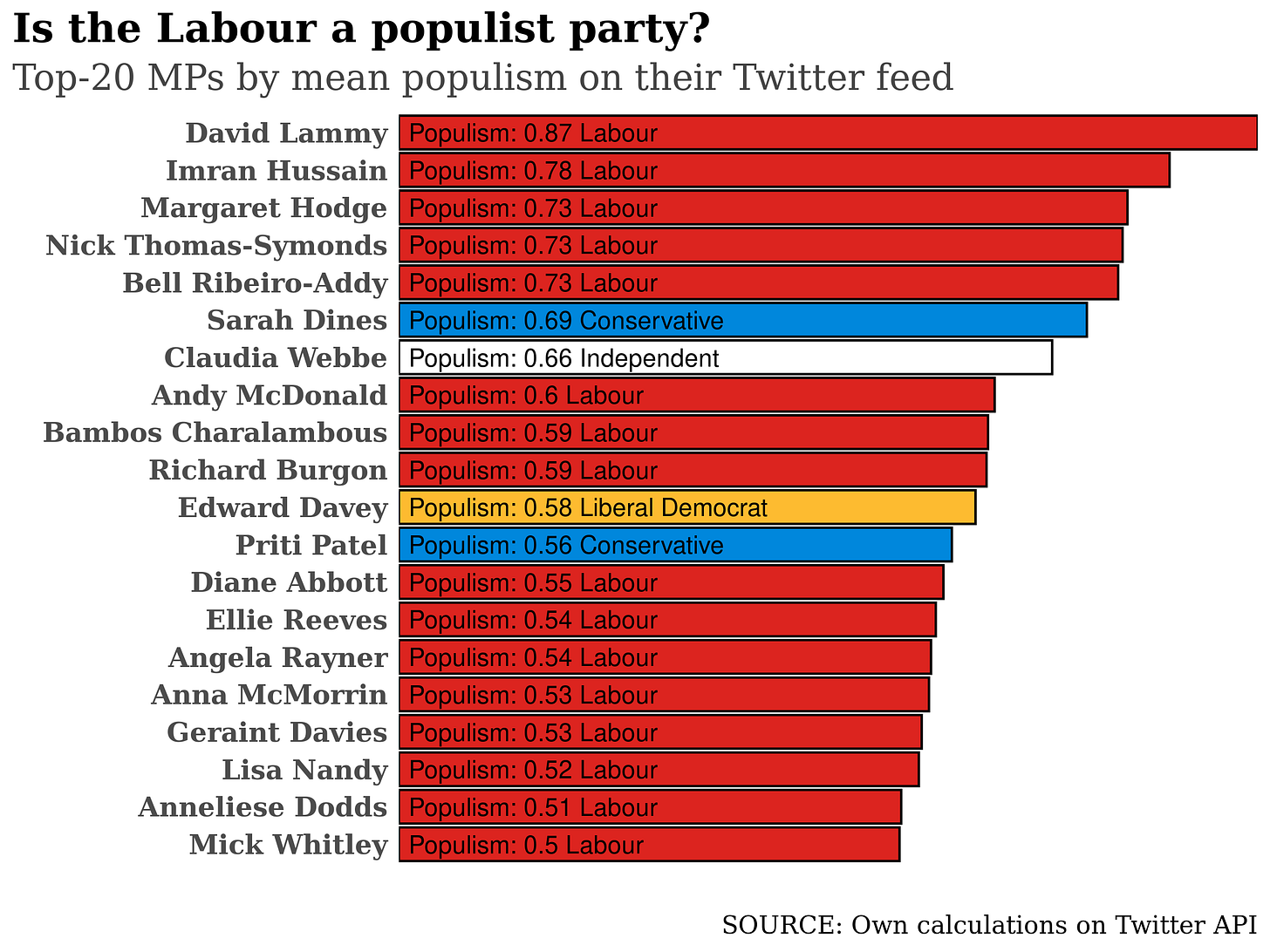

On Twitter MPs, particularly in the Conservatives, have their own degree of specialization. A look at who is in the top-20 most populist MPs will help to explain this point better.

As it could be expected, this top-20 is dominated by Labour MPs. The notable exceptions are Priti Patel and Sarah Dines. The Home Secretary and the Parliamentary Private Secretary to the Prime Minister are arguably the harshest Conservatives on social media. They fit within the general idea that right-wing parties are populist. The real anomaly is that the two of them managed to keep their seat in the 2019 election, although apparently, the General Election did not reward the populist tons, as the following chart will show.

Here DaNumbers collected MPs by the results of the election and Populism. Conservatives stole constituencies to the Labour using a soft-tuned tone of voice persuading centrist voters to go with Boris Johnson. The Scottish National Party is even more interesting. Given its nationalist ideology, it can afford to have MPs stealing seats from Labour or Conservative constituencies. It looks like SNP candidates adapted their social media communication to their voters. The size of the points represents the readability scores, and it doesn’t have any effect on the electoral results.

On the other hand, Conservatives look more coherent, with only a few outliers that fuel the speculation that the Tory strategy is to allow a few frontbenchers to be strong on Twitter, capturing more votes and dragging the party nationally. In contrast, the mass of backbenchers keeps a low tone, keeping local constituents calm and, above all, not scared.

The last chart also suggests that Labour has a strategic issue. If we assume that politics is polarized, the Labour is doing a sensible thing, focusing on keeping its constituents together, thus using strong rhetoric which, in theory, should rally voters around a common cause against the Conservatives. But, at least in 2019, this strategy failed. In fact, according to the last chart, it looks like some voters got scared and decided to ditch the Labour and elect Tory MPs.

Two years into the pandemic and after Brexit, the British political landscape looks moving. According to the latest YouGov polls, Tories and the Labour are separated by only one percentage point. Although the British research institute is not trying to predict elections on a constituency level, polls suggest that the Labour strategy might look not too farfetched, even if what happened in 2019 is difficult not to consider.

Will the Red scare strike back in 2024? Nobody knows, but the fact that Labour is still (slightly) behind the Conservatives might show that the Keir Stramer-led party might still have to fine-tune its social media strategy if it is serious about winning elections in the future.

Here is the R code I used for this analysis.

A certain twitter handle can be found here as well ;) @CheapCrass

Here is my Uber for Urns story. I'm not sure what to do with it so any suggestions you might have would be greatly appreciated. Again, Thank you so much for your encouragement! https://candice372.substack.com/p/uber-for-urns