There is not enough data about lobbying in Brussels

Although European institutions publish some information turning it into data is an impossible task

Dear readers,

This newsletter addresses the substratum of the Qatargate, the corruption scandal rocking the European Parliament. The focus of this episode will be not much on data per se but on how the information is reported and transformed into data. The bottom line is that the way European Institutions report on lobbying and meetings should enter the XXI Century and use better reporting techniques, open data, and standards about technology and information collection.

On a personal note: apologies for missing the November episode.

MASSA MARITTIMA – The relatively small bubble of Brussels professionals is in shock. Even if the scandal's size is not terminal for European Institutions and, perhaps, something entirely predictable by the current state of affairs, the substratum of the crisis has more to do with the implementation of transparency rules rather than with the rules themselves. Why? The following chart will help explain.

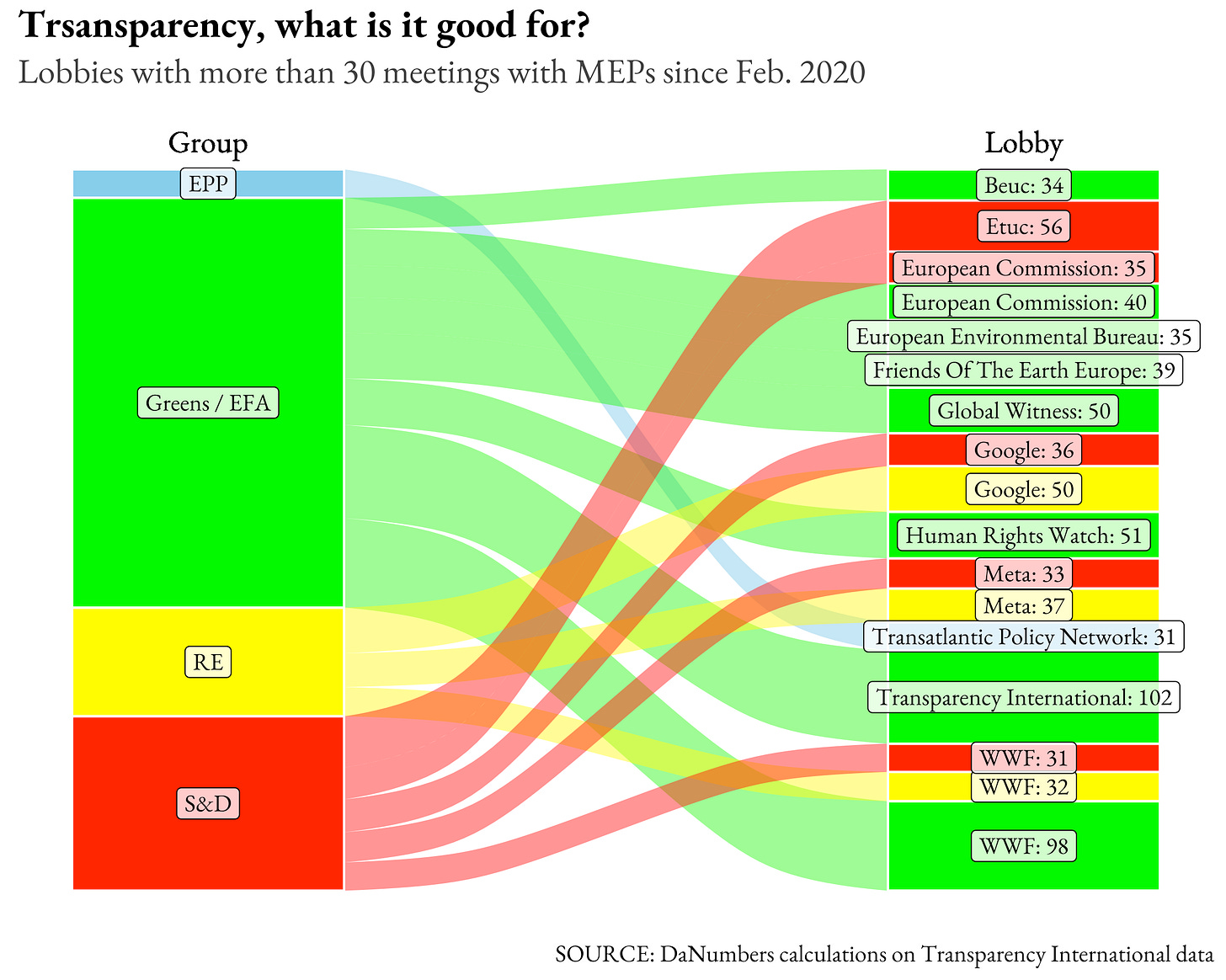

This newsletter publishes a purposely misleading chart for the first time in DaNumber’s history. This alluvial diagram (a variant of Sankey charts) displays the lobbies with more than 30 meetings with MEPs, divided by political groups at the European Parliament. DaNumbers took data from the Transparency International open data portal for the Integrity Watch project: the NGO scrapes data from the MEPs web profile and collects data that can be explored there. With funding from the European Commission, they fill a gap the European institutions should have filled themselves. The original dataset presents its problems, as the code shows here.

Given that it is up to MEPs to report, the quality of the reporting is often low. For example, it is hard to count how many times MEPs met Google representatives. Sometimes, they report meetings with “Google representatives” or the search engine's national branch. More interestingly, they report meeting with Google, not with its parent company, Alphabet.

The same happens with other firms: BNP-Paribas, the French financial behemoth, is listed with four different names; ENI, the Italian oil giant, is sometimes reported as ENI or ENI S.p.A. This does not help to understand who transparently met whom.

Most importantly, given how MEPs and their staff report meetings, firms, and other stakeholders are often hidden among others: MEPs deliver lists of participants to meetings requiring further elaboration by researchers.

The lack of a standardized code to report on the meetings with lobbyists is a widespread problem in the Brussels bubble, not helping with the lack of transparency regarding lobbying activities. After 100 lines of code, all DaNumbers could find was that the Greens met with the WWF, Transparency International, and other politically unquestionable lobbies. In contrast, the Renew Europe group talked a lot with Big Tech. This is not enough. You can read this Wikipedia page for a primer on the ideology of groups.

The visualization above is misleading because the alluvial chart highlights activities with headlines-moving organizations. Trying to dig deeper, the story becomes even more interesting. Using the Integrity Watch by Transparency International, Eva Kaili, the Greek MEP in jail for the scandal, appears to have met none since 2020. Using the online tool provided by the NGO, the keyword “Qatar” yields 20 results. Only three led to Marc Tarabella, one of the MEPs involved in the scandal.

The last Qatar-related meeting was on August 30, when the Belgian MEP met representatives from the Christian NGO Open Doors International, which collects information about religious persecution against Christians and considers Qatar not very different from China. The database also reports on meetings with the Qatar government representatives and discussions regarding the World Cup with the tournament's organizing committee by several MEPs.

In total, since February 2020, MEPs recorded 29,591 meetings with lobbyists. The data are essentially self-reported and rely on the good faith of MEPs. The European Parliament requires only Commette Presidents and Rapporteurs to report their meetings. Many MPs with no roles meet stakeholders anyways. Data from Transparency International yields the following chart.

Here we see the share of meetings by a political group through the role of the single MEP. The result is that most of the time, MEPs met with stakeholders without chairing any committee or reporting on pieces of legislation or opinions. The chart displays that the Greens were the most transparent in their reporting, but it does not add further information.

Transparency International appears to have given up on digging into the data further, given the report they issued on December 5, 2022. Their results partially match DaNumbers's findings, describing the Greens as the most transparent of the Eurochamber's primary caucuses, but they do not explore the counterparts of MEPs.

Low-quality data all over the place

The Transparency International-collected dataset lacks an essential feature. Organizations in the Transparency Register, the database where entities dealing with EU institutions should register, are arranged using a numeric code.

That code should be the key to allowing the lobbying datasets to connect. Missing that link, the data we have can’t be put in a network. This is why it is so hard to match data from the European Parliament (via Transparency International) to data from the Transparency Register, as issued by the European Commission.

This data has problems because the data from the European Commission are not released in a proper open format: the last version of the dataset regarding organizations is released in XML. XML stands for “Extended Markup Languages,” a pillar of the digital world. The following chart will help readers understand how it works.

In practice, in a document, the XML format allows having multiple nested items one within another. This is great if you want to develop an interactive page with this information: this nested format allows developers to display information within menus and sub-menus. The real problem comes when someone tries to understand what this amount of information represents, building a machine-readable dataset.

We just saw a loose representation of how the documents that store information from the Transparency Register work showing only one small portion of the nodes it has. In spreadsheet terms, the columns are on the far right-hand side of the chart: this is where the accurate information is. The rest is a game of Chinese boxes: there is a bigger one, progressively smaller ones.

This node-based structure brings its set of problems: nodes are set arbitrarily in terms of data structure or names. This means that researchers trying to understand these data need to manually un-nest the nodes of this XML document via a trial-and-error process that is difficult to complete without prior knowledge of the implied taxonomies. Some of this process is enshrined in the code of this newsletter, and it offers a blueprint for those interested in making these data openly available via R.

This reflects in the way the financial data are accessible. DaNumbers could reconstruct only part of the financials of 4,509 organizations. And it did so with a superficial confidence level in its findings. The analysis focused on the grants and the budgets for the closed year. In a perfect world, data should be per fiscal year. In this context, the European Commission reports data for the closed year as specified by organizations in their bylaws.

We see above the representation of the top 10 organizations per money in their budget or as a grant. Although this comparison could sound like orange and apples, it shows how organizations display their financial data and the problems it entails. For example, the University of Catania received grants for 19 billion euros. The French agricultural social security fund leading the list claims it had a budget above 30 billion euros.

The German Research Foundation reported a budget of 3.4 billion euros, with American philanthropies reporting budgets between 4.5 and 6.5 billion. The problem with this data is that they do not tell anything about how much they spend, specifically on lobbying. To do so, 8,722 organizations declare brackets for it, DaNumbers computed.

The Corporate Europe Observatory, a primary lobbying watchdog, revamped its data portal in September 2022, trying to provide the budgets of registered organizations. Yet, these data are estimations as even the corporate watchdog claims that the data are “dodgy.”

The European Commission does not publish these data in CSV or JSON. The most accessible it gets is via Excel files (a broadly available but not so open-source format). The Excel file is updated roughly every June, information from the EU open data portal says. The data used in this section are from December 12.

How many are there?

The sheer numbers of the Brussels-related bubble are not easy to find. The watchdog Transparency International esteemed 25,000 lobbyists in Brussels in June 2017. The Dec. 12 version of the Transparency Register counts only 6,535 individuals, including the author of this newsletter. Where are the circa 19,000 more NGOs esteemed? Perhaps, in the offices of the European Quarter where it is not given that organizations have all their employees in the Register. The following chart, though, will help to understand a few things about the European bubble in Brussels.

This chart shows the number of people in the Transparency Register per organization. The colors represent the different kinds of lobbying institutions. Labels indicate the top 10 organizations with the most people in the Register; eight are consultancies.

Organizations in Brussels are complex entities. Behind the person going to the European Parliament or to the European Commission to advocate for particular interests, there is a group of professionals drafting policy, communicating, and, in general, supporting the lobbyist going to the Parliament. Also, the proceeding is not easy: registered people have to provide documents (like a certificate of employment or a statement in case they are freelancers) proving that lobbyists have a legitimate interest in interacting with the institutions.

There is a reason consultancies have so many members registered in the Transparency Register: they work for third parties. This means that whenever someone needs to make a message heard in Brussels but does not have the resources to do it by themselves, they can use these firms with specific skills to do the job. Of course, it is not free, yet, for some, it is a more efficient way to outsource a presence in Brussels. Yet, the role of consultancies is limited if we consider how many organizations are in the Transparency Register. The following chart will help with that.

The most significant number of organizations in the register are NGOs: as of December 12, they were 3,477. For-profit organizations represented less than one-quarter of the Register's total organizations: 3,022. In the Register, there were only five entities by non-EU countries, whereas networks of public authorities represented only 3.6 percent of the total.

The bottom line

Bringing interests to the European Institutions is crucial for the bloc’s democracy: how can policymakers decide appropriately without input from those affected by their decisions? The problem is that the way the process is made transparent is, at the very least, archaic. Particularly for the European Parliament, it prevents citizens from getting clarity regarding who meets whom. It could be better.

To begin with, the Parliament should start giving the meetings by MEP in an open data format. Releasing this information on MEPs pages is not enough: citizens, professionals, and the media need a real-time record to understand what happens at the EP.

Secondly, staffers and MEPs should report their meetings consistently. There should be internal forms where they can, for example, select organizations from the Transparency Register list and publish the id code of organizations. If these entities are not in the Registry, it should be pointed out at the very least. This would not solve all the problems of the Parliament, but it would, at least, show some goodwill.

The European Commission should be slightly more demanding in its reporting need when organizations join the Transparency Register. For starters, it should stop using XML to present data about lobbying and use open-source and accessible formats like CSV. Secondly, it should stop asking for budgets in terms of lobbying or make its declaration compulsory because it would cause the exclusion of registrants from the Registry.

This move might push away some of the more prominent firms and add a further level of informality, but could big multinational groups afford the backlash of not complying with the EU transparency rules? This is an open question.

Could these changes have prevented the Qatargate? Maybe not, but they could have made spotting wrongdoing easier.

ottim analisi da sviluppare i rimedi almeno quelli istituzionali