What Vladimir Putin destroyed in Ukraine

Ukrainians were trying hard to build a democracy before the war

Dear reader,

This newsletter does not propose fancy statistical methods. Here I try to listen to the voice of Ukrainians before the war. Using data from V-Dem and the World Values Survey, I tried to figure out at what point was democracy in Ukraine. To me, the results are heartbreaking: despite some evident contradictions, Ukraine was trying as hard as it could to be ‘like us.’ This makes Vladimir Putin’s war even more unacceptable. Why? Keep reading.

BRUSSELS – There is a heartbreaking detail regarding the invasion of Ukraine by Vladimir Putin: the fact that the Ukrainian society was turning itself into a democracy at the institutional level and as a society. Netflix’s documentary about the Euromaidan protest in 2014 catches this change perfectly. Despite some contradictions, Ukraine looked poised to become a real democracy until Russia started mutilating the country’s territory, as data from the World Value Survey show.

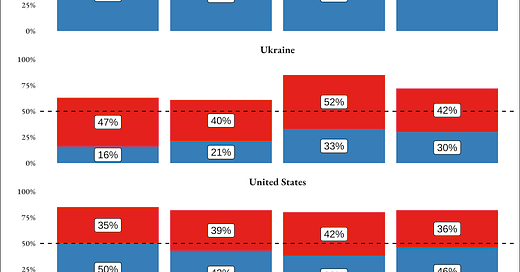

The World Value Survey is a global public opinion poll that tries to investigate what people – globally – believe. The poll works in multi-year waves that are on the horizontal axis in the chart. Here DaNumbers choose to display data for five waves and five countries. Here, Sweden is considered as the ideal-typical liberal democracy. The U.S. is represented because of its leadership in the democratic world. Poland is Ukraine’s successful neighbour; Russia is the invader. The chart above offers insights on Ukraine’s relationship with democracy.

Before the last wave, 85 percent of Ukrainians thought democracy was good. Perhaps, the ineffectiveness of the West and of the Ukrainian leadership to reverse territorial mutilations after 2014 led to some frustration against democracy. That would explain the drop, but there are also more tidbits here.

Ukraine looks a bit more disillusioned than the United States. Polish people think democracy is good despite the far-right PiS government, whereas Sweden confirms itself as a democratic stronghold. Russia, on the other hand, looks the least interested in democracy. Democracy is deemed as very good only by 21 percent of Russians, nine percent point less than Ukrainians. How does it translate in practice? The following chart will show.

Here DaNumbers used V-Dem data to assess the freedom and fairness of elections. Variables from the V-Dem dataset are aggregations of expert-surveyed variables: the Gothenburg-based institute asks political scientists worldwide a very complex questionnaire that translates into indicators like the one that measures the freedom of elections.

The analysis results show that pro-Western administrations lead to better elections in Ukraine. The problem is that Ukrainian elections were not yet up to standard. In 2019, while assessing the presidential election, the OSCE wrote in its assessment:

“[…] the election “was competitive, voters had a broad choice and turned out in high numbers. In the preelectoral period the law was often not implemented in good faith by many stakeholders, which negatively impacted the trust in the election administration, enforcement of campaign finance rules, and the effectiveness of election dispute resolution […].”

Taking Sweden, where the ideal of free and fair elections is practically respected, as a benchmark, it is clear how far Ukraine needs to go to become a real democracy. Yet, Ukraine is the only one improving among the sample of chosen countries. The U.S. saw its electoral process deteriorating – mostly because of redistricting in Republican-controlled states. Poland also reported issues with its electoral process.

On the other hand, this country shows that, given the proper context, democracy can flourish. The Russian case is emblematic: electoral freedoms have constantly deteriorated since the 1990s. This alone should be enough to deem the country an autocracy. This aspect is even more clear reading data regarding the status of political opposition.

Here V-Dem scholars measure how free opposition parties in the chosen countries are. In 1999 Russia looked like a Western country from this point of view. Vladimir Putin’s regime destroyed the feeble democratic process of the country.

Established democracies allow opposition parties to be independent and free. This was also true for Ukraine after the Orange Revolution. After, the government made life harder for opposition parties but not as hard as in Russia, where oppositions rights are minimal. Yet, Ukrainian society appears to have ambitions to be a democracy, as the following chart will show.

The above chart uses WVS data. It shows only the most positive answer to the question about the importance of democracy. Considering the entirety of the scale, all the countries in the sample indicate that democracy is important for more than 50 percent of the population. That’s why DaNumbers focused only on the most positive answer.

The interesting point is that Ukrainians look more disillusioned than Americans. It is hard to blame them: fifty years under a foreign and brutal regime, followed by a fragile presidential system. Yet, the Ukrainian 44.1 percent is almost double of Russians. In Sweden and Poland, democracy is considered very important by the majority of the citizens. In Ukraine and the United States, it is a plurality. Does it mean that the road to democracy will be an easy path for Ukraine after the war? A further chart will offer some insights.

Here DaNumbers measures the level of acceptance of homosexuality. What we see here is a cleavage between Western and Eastern Europe. This is, by the way, the only chart where Russia and Ukraine look somewhat similar. Gender issues are not per se an indicator of how democratic a country is, but this chart shows how the full adoption of Western values was yet to be accomplished in Ukraine. This does not mean that Ukraine deserves to be invaded by Russia: quite the opposite.

In fact, these data have shown so far that Ukraine was on a complicated and contradictory pattern toward democratization, as demonstrated by the previous issue of DaNumbers. Also, Ukraine was starting to do reforms to limit the power of its own oligarchs. It started programs with the EU to boost the rule of law in the country, and, before the war, it was trying very hard (at least) to become like us, despite some issues.

The war put paid to this, transforming a promising country into rubbles. It is hard to imagine what will be of the Ukrainian society once the war ends.

Here is the code I used for this newsletter.

Before you go, some news. I am joining the Estonian firm Evocon, where I will run their content operations. Maybe in the next issues of the newsletter you will read some manufacturing news. Moreover, next week’s Quantum of Sollazzo will interview me. This newsletter is the reference point for everything about data and constantly picks up my work.

Thanks for the attention,

Francesco

CORRECTION: A previous version improperly named the organisation monitoring elections.