Und Bach? A data-driven Odyssey into the Well-Tempered Clavier

Is there a difference between harpsichord and piano recordings? It's complicated

Dear readers,

This is a very special episode. For once, I do not write about politics, but I will deal, again, with music, but this is not the only reason why this episode is special: we recently passed the mark of 600 subscribers. Most of them come from the Anglosphere – quite an achievement considering that I am not a native English speaker. This relatively small number makes me very proud also because this newsletter is becoming more and more inconsistent in terms of publishing schedule. This means that I must reduce the rate of publication to once every three months, formalizing what is de-facto already a reality.

Thanks for your confidence, and for your understanding.

BRUSSELS — If you haven’t heard at least one of the tracks DaNumbers analyzed in this newsletter, you probably have never been on Planet Earth. This issue, in facts, deals with one of the pillars of Western civilization, the Well-Tempered Clavier by Johan Sebastian Bach. This monument of Western classical music was published in 1722 and it has a very basic structure: a prelude, and a fugue for each note of the chromatic scale. The infamous C Major prelude everyone heard in multiple relaxing playlists is the first piece of this collection.

This story will mimic the Well-tempered Clavier’s structure. This newsletter will have a Prelude where we will discuss the findings and the methods, whereas the rest will be in the fugue. Like Bach’s music sheets, our fugue will have an Exposition where we will discuss the data, an Episode, where we will try make something with them, and a Development, where we will provide a wrap-up.

Prelude

The research question DaNumbers tries to answer here is very simple: can we spot the differences of interpretation by pianists and harpsichord players in terms of interpretation, and replicate the findings elsewhere in Bach corpus of musical literature? Using statistics and Spotify data the answer to the first part of the question is yes – it is complex, whereas the answer to the second is no, or, at least, no with the methodology we are about to outline.

To reach these conclusions, DaNumbers collected an impressive group of performers, between pianists and harpsichordists. These are their names:

Piano

Glenn Gould: A Canadian legend of piano, he defined the standard for pianists approaching JS Bach.

Maurizio Pollini: The 81-years old is another legend of piano. His recording of Beethoven’s 5th Concerto is one of my favorite music recordings ever.

András Schiff: Award-winning Hungarian-British pianist

Daniel Barenboim: Conductor and pianist. Despite having been a fierce opposer of philologically informed music performances, his musical career and intellectual standing doesn’t need introduction. For reference, just Google ‘Divan Orchestra’.

Harpsichord

Ottavio Dantone: One of the best-known names in baroque music. His ensemble gave the world some of the standard records for pre-classical music and he is one of the best keyboard players the author of this newsletter has ever witnessed live.

John Butt: One of the best British harpsichord players. Not mainstream, bit his records give the reader a very informative interpretation of what we know now about how Bach was played back in the days.

David Ezra Okonşar: Turkish-Belgian composer and pianists. Spotify has a recording on his name on the harpsichord, making him a precious outlier in this group.

Steven Devine: Director of the Oxford new Chamber Opera in the U.K.

Averaging data from Spotify, some differences emerge among piano and harpsichord players, as the following chart will show.

This Cleveland Dot Plot shows some of the variable that the Spotify’s proprietary algorithm computes on every track on the platform. The general idea is that harpsichord players tend to paradoxically more expressive than pianists: their tracks have more Energy and Valence (joyfulness), whereas pianists seem to aim more to a romanticized interpretation of Bach.

In other terms, this chart seems to suggest that modern performers tend to hide the real nature of baroque music in general, which is to be louder and, in a way, more emotional than people expect.

Exposition

As harpsichordist and conductor Silvia Gasperini once told me, ‘Baroque music is more similar to rock than we might normally assume.’ It had to be so: harpsichords, as musical instruments, are not loud in the first place; secondly baroque music was about to impress the audience. In more correct terms, they had to affect listeners somehow. And, according to preliminary data, harpsichordists are concerned with generating an effect playing more energetically than pianists.

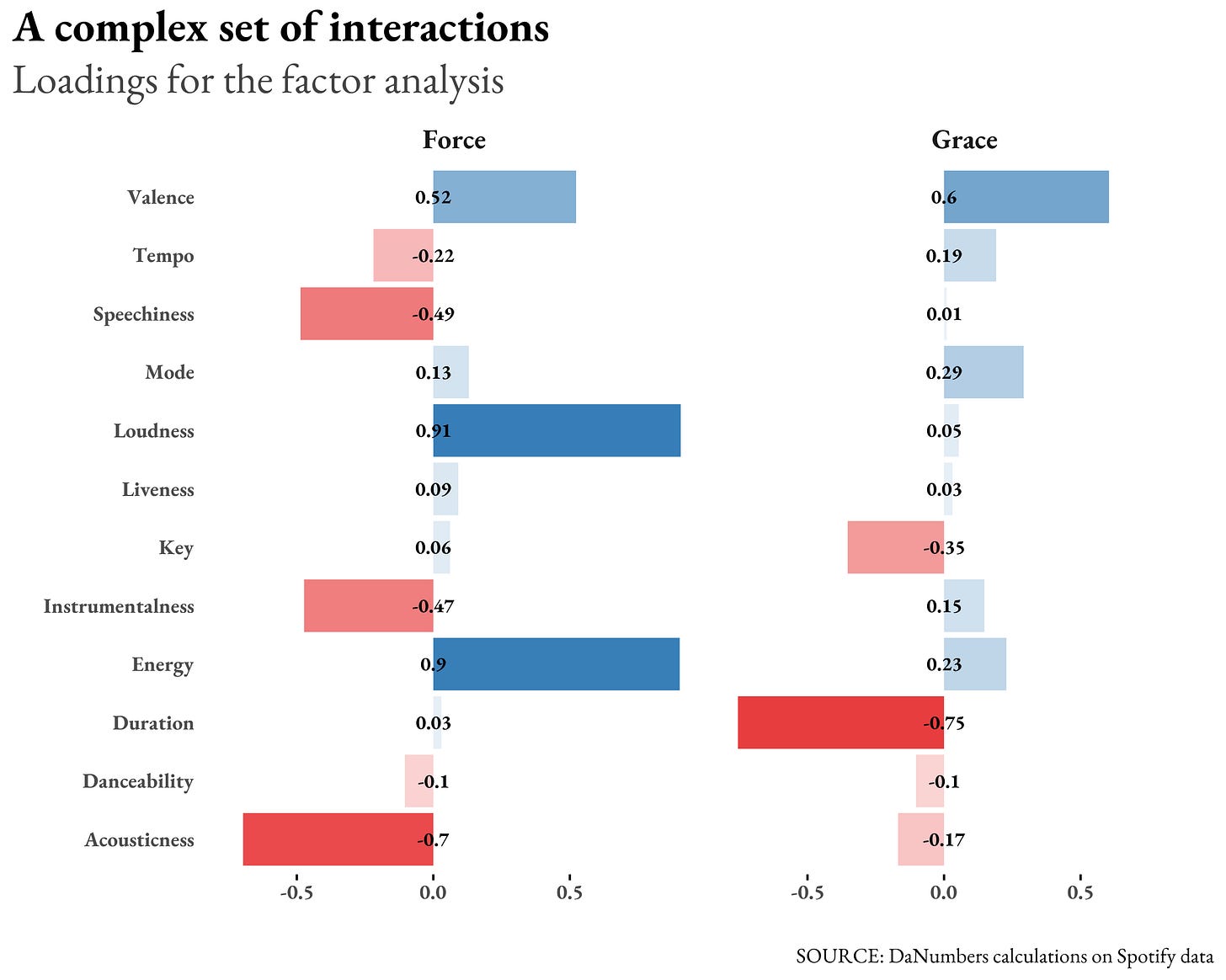

Using a statistical technique which DaNumbers uses every time it can, factor analysis, the variables from the first chart can be compressed in two of them, without losing much information. For the following chart, DaNumbers identified two factors: Grace and Force. How do they interact? The following chart will show.

Here, we add further information from the first chart. On aggregate, pianists and harpsichordists tend to be on the same level of grace, roughly. What really changes, is the force harpsichord players put in their efforts with David Ezra and Ottavio Dantone approaching, roughly two.

This chart appears to describe two fundamentally different philosophies in approaching the Well-tempered Clavier: on one hand, harpsichordists tend to be rougher (more metal?) than their counterparts, pianists try to be more profound, giving one of Bach’s masterpieces a more nuanced interpretation. Evidence of this can be found in the following chart where we will study standard deviations.

A standard deviation tends to measure how far, given an average, the two extremes of a distribution. In other words, if we say that our average speed on a highway was 100 kph with a standard deviation of 20, it is likely that our top speed was 120 kph whereas our lower speed was 80. In our case, standard deviations are useful to highlight how pianists tend to have more interpretative tools in terms of grace than their colleagues on the harpsichord.

Ottavio Dantone, in this sense, is an outlier. His effort, listening to the records, is to give an extremely nuanced interpretation of Bach with style choices which are not always expected, but perfectly fit into the baroque vibe of JS Bach.

In general, harpsichordists seem to sacrifice some originality to pursue a more standardized (or personalized) version of the Well-Tempered Clavier: they standard deviations are, in general, low. Among pianists the outlier relative to this generalization is Glenn Gould. The Canadian legend seems to have developed a very recognizable style which might raise some eyebrows among the purists but, at the very least, helped popularizing JS Bach works.

Pianists tend to play Bach less loud than pianists. This might be because a piano hits strings with a hammer, rather than plucking them as a harpsichord does. This means that pianists, when playing Bach, can do pretty much whatever they want: they are not forced to display a very good articulation of their hands and to play as surgically as a harpsichord performer: they can have more fun – that means more freedom.

Despite that, the music sheets of the Well-Tempered Clavier are the same for piano and harpsichord. This is why we could confidently perform a factor analysis of the Well-Tempered Clavier. The methodology is interesting because we took the first 24 tracks of the recording by our artists. In some cases, like Ottavio Dantone and Andras Schiff records the preludes and the fugues together. This shouldn’t be a problem because the notation is just the same for everyone. This is why we didn’t find problematic pulling them together. We will discuss the results of the factor analysis here.

The results of the factor analysis as such tell us that interpreters of the Well-Tempered Clavier tend to match playing louder to higher level of energy and joyfulness (valence). On the other hand, Grace is mostly characterized by shorter tracks and a more joyful attire when recording. For this factor analysis, we could have pushed up to five factors, but DaNumbers made the choice to keep the analysis simple and neat.

Episode

If in the Exposition we gave a description of the differences between pianists and harpsichord players, here we will see if those differences are enough to predict a track is played by a piano or by a harpsichord.

For this analysis, we used a logistic regression. For a logistic regression, imagine tossing a coin: what are the factors (wind, number of times it flips) that make this coin land on its head or on its tail? For more on the logistic regression, Wikipedia has a very dense page on it. Details will come from the following chart.

This chart is an experiment: logistic regression should not be represented like that (particularly knowledgeable people might notice that there is not a logistic curve in this chart), yet it offers a lot of insights, not only on the fitness of the model, but also on the difference between the single artists in the sample.

To get to this chart, DaNumbers used Grace and Force as predictors. For the logistic regression, we sampled 30 tracks out of 192. Then we deployed the model on the rest of the dataset, measuring the probability the instrument is a piano. The bottom line is that the model understands better when it is not a piano (hence it is a harpsichord) rather than it is a piano.

In some cases, like Ottavio Dantone, the score is perfect. In other cases, things are a bit fuzzier. On the harpsichord size we have four tracks that the model interprets as likely related to a piano, on the piano tab, there are nine tracks by Maurizio Pollini and Andras Schiff with a probability it is a piano lower than 50 percent. Glenn Gould couldn’t anything else but a pianist here, with all his tracks solidly above the 60 percent of Probability.

In general, the chart shows that harpsichord players tend to be more recognizable as a standard than their counterparts. This chart also proves again that pianists tend to play more freely. Some might argue that they even introduce parts of the philological research of harpsichordists and musicologists in general in their executions. In fact, some of Pollini’s records feel like there are played on a harpsichord – the model argues. But is it really the case? The following chart raises some questions on that.

Before going into the chart, we need to brush-up our knowledge of musical theory. A minor scale, literally, is a sad one. What makes it sad, is a shorter distance between the first note and the third note. This is why the E is flat: on a major scale, it is natural. B, in minor scales, should not be natural: it should be flat but, usually, it is only while descending. The reason is simple: when you go up, you need to get back to the first note (albeit on a higher octave); to do so you need the seventh note to be very close to the first of the following octave.

Given that the prelude in C-minor is a musical journey around C, it makes sense to understand what note one interpreter sees as the key for the piece. This is why the chart is so important in this context: it gives us information on what pianists and harpsichordists are trying to tell.

In general, harpsichords play a lot on the B. That means that, for them, this prelude is mostly about movement; it is a tension towards finishing on C rather than beginning on it. This is particularly true. Andras Schiff and Ottavio Dantone are missing because they record Prelude and Fugues together. David Ezra – a pianist by training – is a bit of an outlier here, where his execution seems to mimic the one by Glenn Gould.

One important piece of information is about the vertical axis: Spotify collects notes on segment, the more segments are there in a track, the longer it is. We can see how Ezra and Gould are similar also in that aspect. Another interesting trait is Daniel Barenboim interest in the E flat.

In general, both fields share a divide in how to interpret this prelude. On one hand, we have Ezra and Gould who even perform it on a staccato, on the other we have all the rest seeing every note as part of a more organic phrase.

The fact that two sides of the aisles take stylistically similar choices adds an element of complexity to an analysis which, for the moment, might seem to be a bit too deterministic, putting harpsichord and piano players in two not- communicating silos. Also, for the moment, we found some generalizations valid for the Well-Tempered Clavier. What If we try to transpose them, say, to the Goldberg Variations? The next chapter will answer.

Development

The theory here is simple: the Well-Tempered Clavier is a very important work by JS Bach. Can we generalize what we found about it to other works? The answer is in the next chart.

Here, we tried to test if a Goldberg Variation track was played by a harpsichord or a piano. The results are disheartening. Out of a sample of 48 tracks, the model could correctly classify only five of them. And in fact, the sample of 48 tracks DaNumbers collected for this test works fundamentally differently than the one about the Well-Tempered Clavier with a fundamentally different definition of Force and Grace, as the following chart shows.

Force, on the other hand, is forceful in a completely different way. For the Well-Tempered Clavier, it is less connected to duration, whereas here duration is one of the main components of this factor. This means that, unfortunately, in this context it is very complicated to find a generalization about how harpsichordists and pianists interpret Johan Sebastian Bach in general and beyond the single work.

A general lack of data (we used relatively small datasets for this story) might be the reason why it is so hard, in this context, to find a general rule but, perhaps, there is something more fundamental than that, as the final chart will show.

The dataset about the Goldberg Variations is composed by recordings of Glenn Gould for the piano and Jean Rondeau for the harpsichord. According to this chart, the Goldberg Variations are approached completely differently than the Well-Tempered Clavier, with Glenn Gould being more forceful than his counterpart.

Is this enough to give up? Probably, with a bigger dataset it could be possible to train a model to determine if a track comes from a pianist or a harpsichordist. For the moment, though, we are forced to contemplate the brilliancy of Bach, who, three centuries later, is not only a perennial source of inspiration, but so great that it can fool today’s hyper-sophisticated machines.

Wow!