The state of play of COVID, globally

Data from the rest of the developing world proves to be problematic

Dear readers,

This newsletter comes after the omicron variant wreaked havoc on what looked like a quick recovery to normalcy. But, instead, the new variant led to an acceleration of the pandemic. To help you track its evolution, I developed a minimalistic tracker. It is a Shiny app that measures the acceleration of the pandemic. It also offers a snapshot of the variants present in EU countries plus other political and policy information. Apart from a few glitches (the map misses Greenland as of now), the tracker provides an angle you hardly find elsewhere.

Since you are here, I launched a small questionnaire. I am asking you to fill it to help me understand your needs better and see if I can turn this newsletter into a more professional effort.

Thanks for your attention and for your feedback and… Happy New Year.

BRUSSELS, Belgium – This year marks the second year of the pandemic. The COVID outbreak started in China in December 2019. More than 5 million deaths later, we are still fighting the virus. The good news is that our tools are up to the task. For example, vaccines might not be the perfect tool to stop the contagion, but they save lives, as the following animation shows.

On the horizontal axis, we see the share of the population with two vaccine doses. On the vertical axis, we see how many people die per million people daily. The chart works like a fountain. At the origin of the axes, it spits countries. Countries move on the horizontal axis and, as they move, the number of people who die daily approaches zero. The chart also demonstrates the deep inequality regarding the vaccination campaign. People from Africa didn't benefit from the vaccine, whereas European countries marched towards high vaccination thresholds.

The chart above is yesterday's news. The focus of media shifted from second to third doses. This tracker's last chart offers information on it. Moreover, the omicron variant led to quicker third doses and talked about a possible fourth for vulnerable people. What happened during the last three weeks proves how difficult it is to measure the effect of policies in different countries—for example, testing. So far, it isn't easy to prove that massive tests allow us to find more COVID cases.

The chart above shows the 20-days average of the number of new COVID cases and the 20-days average of tests per case. Countries that proportionally tested more are not associated with more cases.

Testing alone does not allow to do an efficient case count. So, we have countries that do a lot of tests like the Emirates, very low on the case-count chart, and countries like the U.K., with a high number of pro-capita cases.

Considering that testing champions are small and wealthy countries (UAE, Taiwan, for example), it is realistic to think that the number of tests remains relatively constant over time. That would explain the drop in the test per case chart: as cases grow, the number of tests needed to find COVID-positives decline. According to this chart, testing does not affect the number of spotted covid cases. Can we trust these data?

This newsletter decided to use Our world in data as a source. The non-profit British open data portal provides datasets from multiple sources. Regarding COVID, it relies on Johns Hopkins University, which collects data from government sources. The problem is that governments don't always put their acts together. In fact, during the pandemic, DaNumbers spotted some quirk stuff going on. More, in the following chart.

Here we collected significant corrections on the OWID dataset when data report a negative daily number of dead people. According to these data, people resurrected from COVID. This kind of inconsistency is not very frequent and, besides Spain, they come from countries with problems in their administration (Peru and Central Asian countries).

Not all governments are equal, so it is not their data collection. This is particularly evident when we explore demographics as a predictor of new cases. The results, in the following chart.

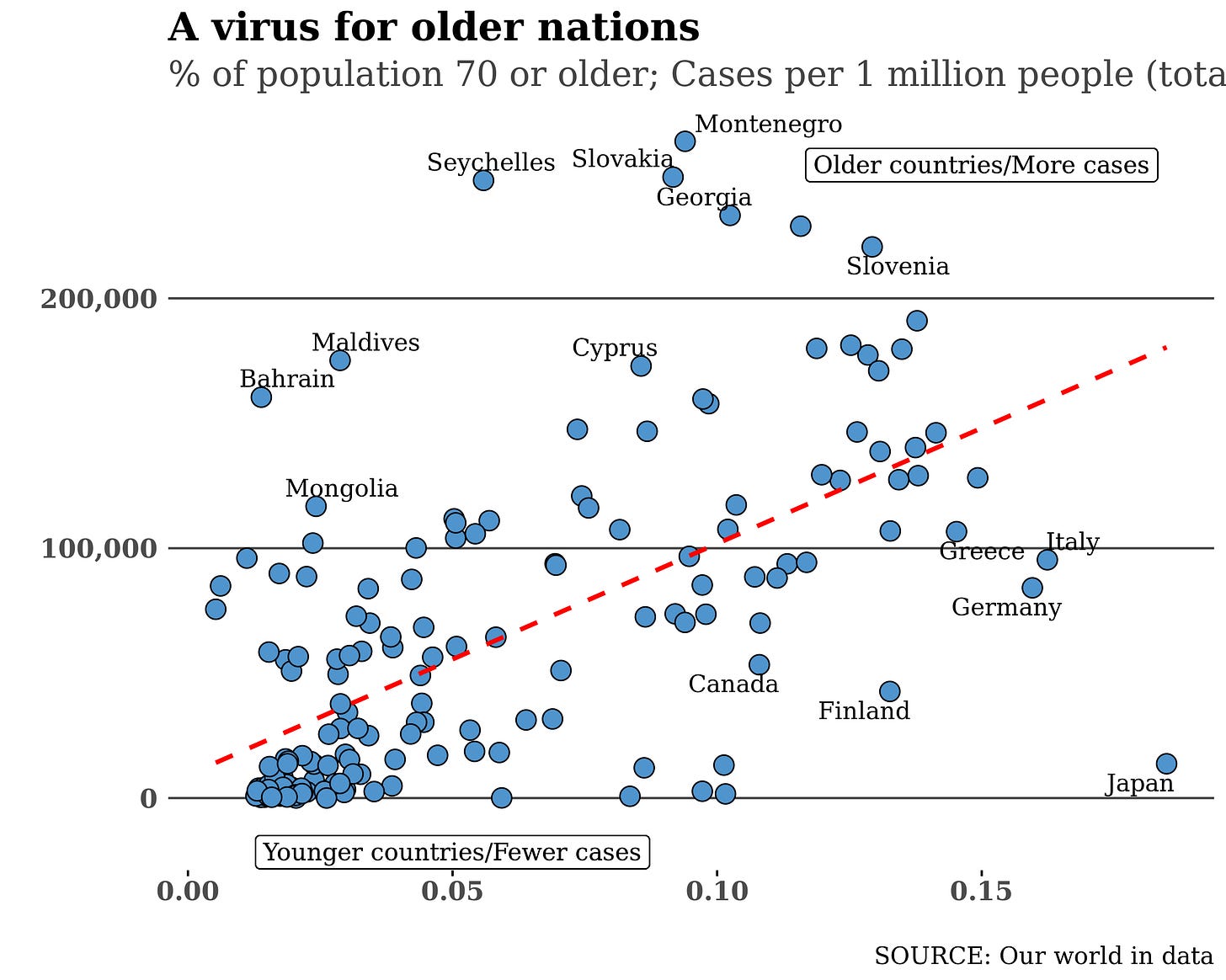

We see here that countries with younger populations tend to have fewer cases than older nations. Browsing within the names, we notice that we have African countries at the bottom left of the chart, whereas European countries tend to be at the top right. According to some healthcare professionals, the virus intrinsically targets older, more vulnerable individuals. Is it the end of the story? The following chart says no.

Here, we see the number of countries with less than 50,000 cases per million in total since the pandemic began; 46 of them are in Africa and 26 in Asia. Is it a mere coincidence, or is it because local governments have fewer resources to track cases, thus taking effective measures? The following chart might give some answers.

In this case, the predictor was the Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI is an indicator developed by the United Nations to measure how good human condition is within a country. With some conceptual stretching, it can be an acceptable proxy to measure the effectiveness of governments: effective governments provide better education, better healthcare, and so on.

According to the chart, HDI is a better predictor than the population over 70. In fact, according to the first scatterplot, each percent-point raise in the share of the older population yields 9,254 cases per million, with the model explaining 39 percent of the number of cases in total. On the other hand, HDI growing by 0.01 gives 2,843 cases in total.

Of course, this is a lower number, but HDI appears to have a stronger correlation with the number of new cases, explaining 47 percent of its variance. Perhaps, we will never know if demographics spared the developing world from the worst of the pandemic.

For sure, the Western world looks better equipped to fight the virus than it was one year ago. It might not be so reassuring for the new year given the current record-breaking surge in cases, but with vaccines, data, and experience, there is hope that in 2022 we will make decisive steps out of the pandemic.

Here is the code used for this newsletter.

CORRECTIONS: This newsletter didn’t link to the code used to produce it. The subtitle of the first animation spoke about new cases. Instead it represents new deaths per million.