The migration from the Former Soviet Union to the EU in six charts

Running away from Russia or their local tyrants? A few insights on the migrants you didn't know about

Dear readers,

DaNumbers goes to a special place for this edition: The Former Soviet Union. For this edition, I took ex-USSR countries and tried to figure out a few things about their migration to Europe. The numbers are small but meaningful and try to shed light on something broadly (and understandingly) underreported but no less important.

Thanks for reading

BRUSSELS — From January 2009 (the first date Frontex data displays) to April 2022, 4,028,547 people from 153 countries entered Europe illegally. Eleven thousand nine hundred seventeen of them were from the Former Soviet Union. This number could be a statistical error, but it sheds light on how migration works and the risk migrants are ready to take to leave their countries of origin. One of the most interesting facts from the Frontex dataset is about Central Asia.

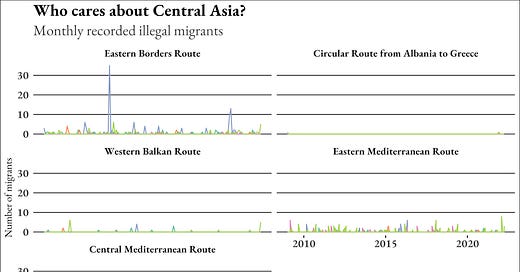

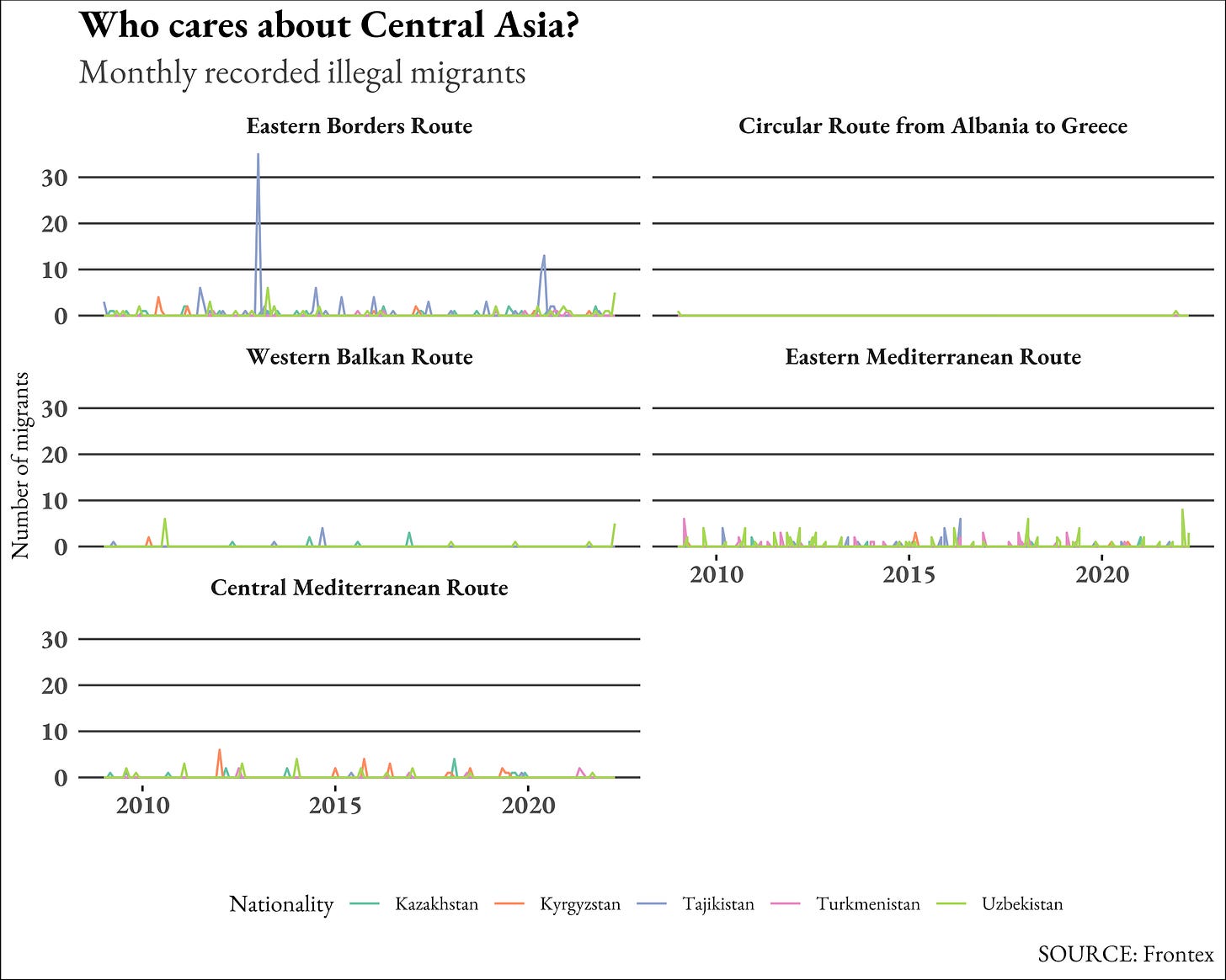

Central Asia is a region where several countries whose name ends with -stan insist. The area had been a target for Russian colonization during the XIX Century, and it was the terrain of that “Cold War” between Tsarist Russia, and Great Britain historians call “The Great Game.” Those countries are landlocked (the Caspian Sea is a lake), and yet, migrants depart from there to come to Europe. Illegal migration from Central Asia to Europe works as the following chart shows.

Numbers are incredibly low. The astonishing detail is a 35-strong Tajik migrant wave in 2013 on the Eastern borders. Other Central Asians, though, follow more dangerous patterns. Handfuls of Kazak, Uzbek, and Kyrgyz ended up on the Central Mediterranean route. Almost none passed via the Balkan-based trails, whereas most migrants passed via land on the Eastern border of the European Union.

Although there is no data available on the routes these people follow migrating from Central Asia, slightly broadening the spectrum, we that before Putin’s war on Ukraine, there was a small but significant stream of people moving toward the European Union from other parts of the former USSR. The following chart will shed some light on it.

The first thing to notice is the number of Ukrainians that illegally crossed the border with the EU in April 2014 in the aftermath of Euro Maidan. Frontex recorded a smaller wave in March 2020. In addition, Russians are present in the Eastern Borders. Russian migrants also undertook the Eastern Mediterranean route to get into Europe.

The chart is relatively inconclusive: the number of illegal migrants is still so low that it is easy to understand why it went overlooked, given the ongoing crises that affected the external borders. Also, so far, we have discussed absolute data. What would happen if we consider the percentage of illegal migrants by route and nationality? The following animation will answer.

In relative terms, the most followed route is the one passing by the Eastern border. Also, most of the illegal migrants coming from the Former Soviet Union are from Europe, particularly from Moldova, Russia, Georgia, and Ukraine. Besides the Eastern Border, the Eastern Mediterranean is the favorite route for migrants from the ex-USSR.

The dots moving at the far-left end of the chart are usually Caucasus and Central Asian countries. The trends follow the political events of the countries of origin. For example, in 2014, in the aftermath of Euro Maidan, Ukrainian became more relevant, as citizens from Belarus became after the last election. This explanation is compounded by what we know about the situation in the countries of origin, as the following charts will show.

Here, we see the share of GDP from remittances. Only Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan depend on remittances significantly. On the other hand, autocratic countries tend to have a smaller impact from their diaspora on their national accounts. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have a long history of migration toward Russia: coming to Europe is more of a political choice, as we will see in the following chart.

This chart shows the level of liberal democracy as calculated by the V-Dem Institute. When it is zero, we have a North Korea-level of autocracy. When it approaches one, the indicator approaches closer to the ideal of democracy. In this case, we see a very complicated picture. Russia, Caucasian, and Central Asian countries report very low scores in terms of democracy.

Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, in this chart, look like extremely complicated places. Russia displays a deterioration of an already weak quasi-democratic system. Kyrgyzstan, once credited as a success story in Central Asia, is not doing well. In contrast, Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova (the three newest countries to receive the status of EU candidate) report relatively high levels of democracy. Armenia saw its democracy improve until the war against Azerbaijan; Azerbaijan looks like a Central Asian country more than its neighbors.

The last chart is problematic. Combined with data from Frontex, the chart suggests a world where migrants run from democracies in the making that do not depend on their diaspora to run their economy. Is that the case? Data about first-time asylum requests could help find answers.

The chart displays only first-time asylum seekers. The data show that Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova are the top three countries, followed by Russia and Belarus. Other Caucasian and Central Asian countries are well represented, with smaller numbers than the first three.

Some figures are easy to explain: Armenia lost a war, the current leadership rigged the last presidential election in Belarus, and Putin’s Russia is what it is. However, this leads to another question: why are so many from the top three? What do these countries have in common?

To begin with, we do not know where asylum seekers are from. As far as we know, asylum seekers could well be from Transnistria or the Donbas. We also know that the number of asylum seekers from the Former Soviet Union is declining. The following chart will show this aspect better.

Here we see the top-5 from the previous chart over time. The generalized drop for 2020 is more an effect of COVID-19 travel restrictions than anything else. We can see a sharp rise of Belarusians (from 1,180 in 2020 to 3,475 in 2021) and a strong rebound of Georgians to 12,775 first-time asylum seekers. Moldova went back to its 2019 levels of around 5,000 people, whereas Ukraine saw a modest rise from 2020 in the context of a sharp decline from 2021’s 8,750.

Despite being counter-intuitive, data suggest that having a conflict with Russia is a possible driver for people to leave their countries for EU countries. The data from asylum seekers also show that illegal migration from the Former Soviet Union is a limited phenomenon. Yet, the two datasets ask more questions than they answer. Among the unanswered ones: why didn’t we pay attention before?