How political leaders declare war

A data-driven analysis digs into one of the most uncomfortable avenues of political rhetoric

Dear readers,

Here DaNumbers tries to use sentiment analysis to see the features of war speeches since WWI. This approach could sound a bit far-fetched, but the interpretation of the data led to some charts which shed some light on how political leaders drag their countries into conflict.

On a personal matter, my career took a new development. I started working as Communications Officer for the European Microfinance Network here in Brussels.

Have a nice read.

BRUSSELS -- War is complex. Since the advent of the industrial era to wage war, political leaders need the support of multiple stakeholders, beginning with their citizens or subjects. What is known as total war needs the commitment of entire societies: the soldiers going to the front lines need to be committed as well as the blue-collar workers manufacturing weapons, for example.

This is compounded by the existential threat of war at the individual and collective levels. Families will lose beloved ones; governments can collapse in case of defeat. In order to persuade an entire society to commit to such a risky business, politicians need to craft their sales pitches very carefully. Here DaNumbers selected 19 of them and, analyzing their sentiment and readability, tries to understand more about how politicians sell war as an outcome to their compatriots.

The sample is relatively restricted because there is not a lot of material available. Public speeches about war look like a fascist thing or a parliamentary issue. In fact, when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, none from the Soviet leadership gave a speech: the only document announcing the start of the operations was a party directive. Similar oddities are also part of this sample, as the chart will show.

For example, U.S. President Henry Truman announced the war in Korea via a press release, whereas Hirohito, the emperor of Japan, declared war by proclamation. On the other hand, Benito Mussolini dragged Italy into World War II from his Palazzo Venezia balcony, whereas most western leaders spoke to their legislative assemblies. Regarding WWII, there are several doubts regarding a speech Joseph Stalin might have given to the Politburo in 1939.

From the second part of the XX Century, though, war declarations changed: U.S. presidents started announcing operations on primetime TV, whereas authoritarian regimes started imitating the West. Slobodan Milosevic, for example, announced the beginning of the Yugoslavian troubles in front of its federal parliament, and, two months ago, Vladimir Putin addressed Russians from his office via TV like any other American president. Did this change affect speeches somehow? The following chart will give some clarity on that.

The above chart shows how easy speeches are to read using the Flesch score, considering how long words are. The bottom line here is that media did not affect speechwriting that much. In the top-5, there are three WWII declarations. Wars from the ’90s (Gulf War and Kosovo) were third and fifth. Adolf Hitler’s speech is third, but it is what happens at the bottom of the line which is interesting.

The most challenging speech to read is Hiroito’s declaration of war. Like all the non-English speeches, DaNumbers analyzed Hirohito’s one in its English version, as published by English-speaking Japanese media at the time. The translation might imply that something got lost in the process, but it is unlikely.

This classification is relatively easy to understand if we take history into account. WWII, the Gulf War, and even Kosovo were easy to explain to citizens. Hirohito was the monarch of an authoritarian and militarist state, but there are some interesting dynamics in the middle.

For sure, the political language of 1914 was a bit more obscure than it was 25 years late: The uneasy speech by Antonio Salandra, the Italian PM in 1915, though, offers some hints on a broader problem: the logic underneath a war. The chart above hints at the possibility that the more complicated a war is to sell to a society, the more complex its declaration is.

Antonio Salandra’s speech fits very well within this category. He had to justify Italy breaking an alliance signed in 1872 with Austria and, most importantly, Germany. Although the final objective of a unified and liberal Italy was a noble proposition, some might argue that the country lacked the political capital to make such a choice, so it had to find a complex explanation.

This is the problem of Vladimir Putin: he had very little to sell to Russia, yet he had to say something. How he (and others) said it is the subject of the following chart.

The order of the speeches is random because it allows visualizing speeches as single specimens. The values in the lend show that the two variables come from an application of factor analysis. Rage and hope come from an aggregation of sentiments like fear, disgust, anger, and sadness. Anticipation, joy, and surprise are aggregated into hope.

This classification shows some interesting traits in war rhetoric. For example, Adolf Hitler’s war declaration amounts to a massive rant where there was very little space for hope and a better future. George W. Bush, on the other hand, after September 11, offered a massively inspiring speech to the U.S. Congress.

Interestingly, Vladimir Putin is between Hitler and Bush. His televised and hard-to-read speech is unique because it mixes rage with hope. This is a similar trait to another unjust and unjustifiable invasion: Iraq. Less than two years after the attacks on D.C. and New York, George W. Bush decided to abandon his inspirational tone and declare war harshly. The last consideration leads us to think that rhetoric is used to mask wrong choices.

In fact, the Salandra war declaration is the one that looks more similar to the February 21 address. As in Putin’s case, the Italian PM had a tough sales pitch to deliver. He showed the alleged wrongdoings of the enemy (the rage part) to justify a contentious policy choice like Italy’s participation in the war. Similarities between the two speeches are not over.

To investigate further, we need to use an element of Russian formalism. During the first part of the XX Century, some Russian philosophers tried to formalize the vast body of folk tales Russian culture is full of. The objective of people like Vladimir Propp was to find a way to represent and describe a story in universal terms. Here is where Fabula (the story’s content) and the Syuzhet (its chronological order) come into play. The following chart focuses on the latter.

Here we see the Syuzhet of four speeches that led to a lot of trouble. We have Hitler’s war declaration, Antonio Salandra’s address to Italy’s lower house, Vladimir Putin’s very speech, and George W. Bush’s speech about Iraq’s invasion.

The values were transformed to have some elegant curves, and they are spread over 100 points. When the curve is above zero, values are positive; when the curve is below zero, values are negative. Three cases out of for finish with a positive sentiment. Adolf Hitler is the exception, and it corroborates the fact that his rhetoric was quintessentially nihilistic.

The striking thing is the parallel between Putin’s and Bush’s speeches: they both use the same narrative strategy. They keep the speech generally upbeat; then they go negative for a while, and, at the very end, they try to rally their audience, promising to win the war.

Partially, the same goes for Salandra. He keeps his tone low for almost three-quarters of the speech before trying to rally the house and bring Italy into WWI. Adolf Hitler, though, ends up very soberly concluding his rant in a very anticlimactic way. Despite this oddity, though, war speeches are more similar than expected when one goes to see the share of sentiment within them, as the following chart will show.

Here we see the real problem with war. People think they can win it, no matter if they are the leader of a corrupt authoritarian regime or a democracy: none want to lose. That’s why they need to rally societies rather than troops.

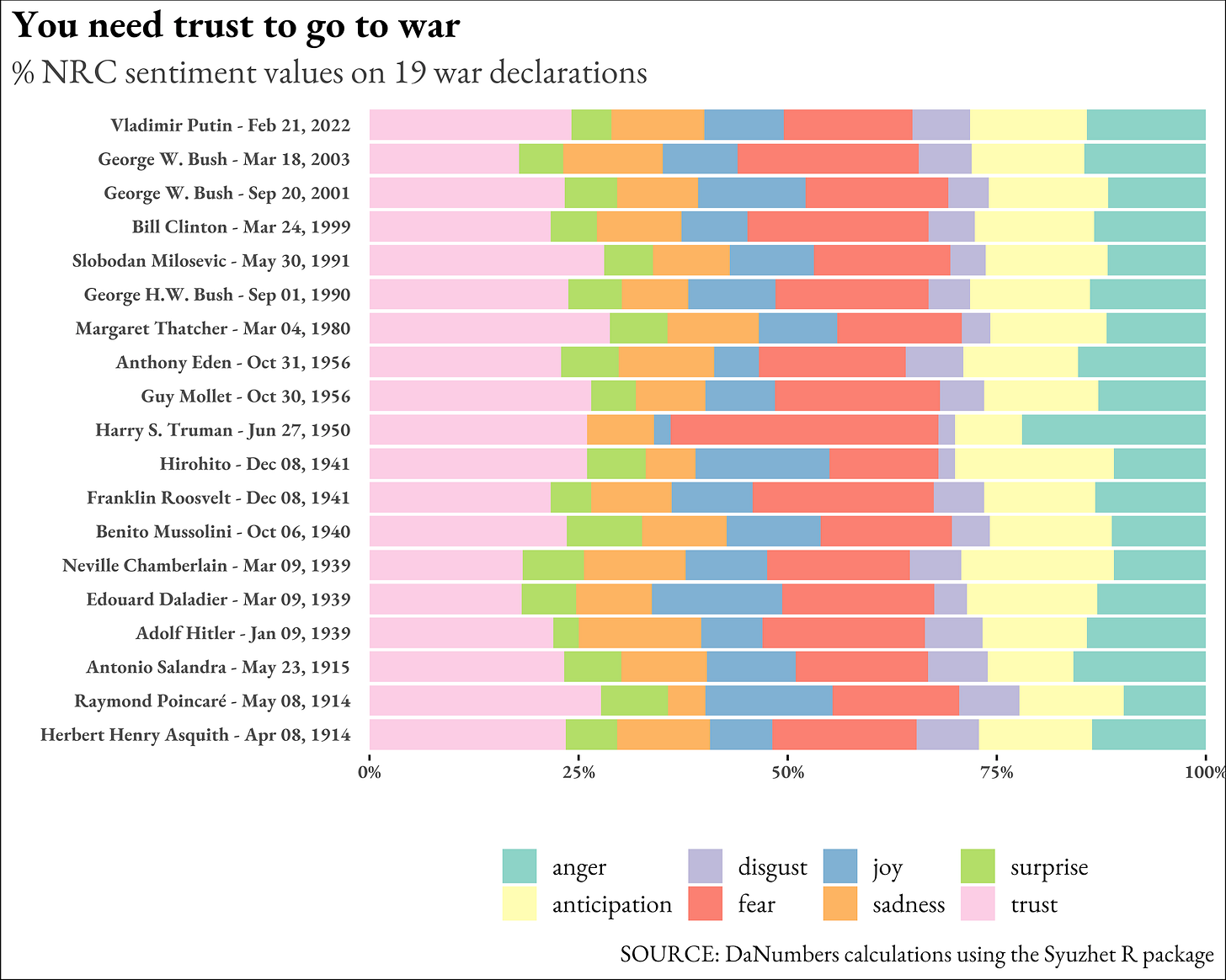

This chart is where the factor analysis comes from. Here a Canadian-developed algorithm measured every war according to the sentiments we see in the legend at the bottom of the chart. Instead of aggregating them, this time, DaNumbers calculated the share of every sentiment. The result is that all war speeches sound the same.

The exception here is Harry Truman’s press release about the war in Korea, where there is a clear fear element compounded by anger telling about the mindset of U.S. policymakers at the beginning of the Cold War when a new world war against communism looked more likely.

Trust values are always around 25 percent. Even Vladimir Putin doesn’t go that far from that value. Yet, even he can’t change the way politicians try to sell a war to their citizens, no matter how good that product is.

Click here for the code used for this newsletter.

CORRECTION: The original version of this newsletter lacked a chart.