European governments push migrants routes elsewhere

Migrants keep dying thanks to NGOs criminalization and strict policies

Dear reader,

this newsletter was supposed to land in your inbox yesterday. It didn’t because last week there was a shipwreck in the Mediterranean and, given the huge amount of data available about migration, I decided that it was worth messing up the schedule, so to provide insights into one of the XXI Century’s tragedies: people drowning in the Mediterranean sea.

BRUSSELS - Before the April 23 tragedy, in the Mediterranean 421 people had already lost their life since January 1, 2021. That number now is now above 551, given that last week approximately 130 people lost their lives in one of those tragedies that have been commonplace since 2011. The Missing Migrant Project by the International Organization of Migration collects data since 2014. The following map shows how things went in 2021, right before the last shipwreck.

Lampedusa, in the centre of the map, is the main point of attraction for migrants. A series of points departing Tunisia ends up right in front of the tiny Italian island. People keep drowning in the Aegean, between Greece and Turkey, but in limited numbers. The Western Mediterranean route is active, with the Spanish enclave Melilla and the coast of Spain as the main points of attraction.

The methodology of this story is pretty cynical: it uses the localization of the dead to highlight migration routes. Also, pinpointing dead and missing allows assessing national migration policies: are governments solving the migration conundrum or are they just pushing the problem away?

Before April 23, there had been 81 shipwrecks. On average, they yielded 5.6 dead people. Roughly, there was one shipwreck every 1.4 days. Yet, some commentators see this situation as an improvement from 2015. A superficial read of the data might support those views.

In the Mediterranean alone, deaths declined sharply. If deaths in 2016 were 5,143, in 2020 they were 1,426 in 2020. This alleged success occurred after a shift in Italian migration policies. After 2015, the favour of public opinion towards open-door migration policies shifted. And, besides targeting migrants, it had a new objective: limiting NGOs’ activities.

Non-government organizations organized search and rescue operations but, at one point, those operations were considered as an incentive for migrants to set sail towards Europe. In facts, after 2016 numerous ships were seized and several trials were initiated in Italian courts against NGOs’ operators. These harsh measures didn’t deter migrants from trying to reach Europe, as the below map shows.

The map shows where migrants died or got dispersed since January 1, 2014. The chart focuses on Central-eastern Mediterranean and internal Libya. This visualization has several points of interest. The first is that in more than five years migration routes didn’t change much: Libya finds itself as the converging point between a route coming from Eastern Africa and another from Western Africa.

The second is that people did not stop dying for migration, no matter how harsh European migrations policies were. The impression, looking at the colours of this map, is that migration policies didn’t do anything, apart from pushing the problem elsewhere, possibly, under the Italian point of view, on continental Africa or westwards, as the following map will show.

The chart above works like a weather map. The circles encompass areas where the density of points is higher than others by year. This allows assessing the effect of migrant policies in the most impartial way possible. Results show that European migration simply relocated the problem, rather than solving it.

As far as Central Mediterranean is concerned, there are several concentric ellipses around the Libyan coast. In 2014, shipwrecks were likely to occur anywhere between Libya and Sicily. Progressively, shipwrecks became particularly common between Tunisia and Libya.

There were also changes in the Western route, with catastrophes progressively moving away from the Gibiltair’s Straight to the coasts of Morocco and Algeria, not far from the Spanish enclave Melilla.

The real exhibit supporting the idea that the Italian and European governments limited themselves to push migrant is the circles in Southern Libya and Sudan. There DaNumbers identified two clusters in 2018 and 2019: migrants, in recent years, died more often travelling on land than they did before.

Migrants didn’t start dying more south. In recent times, the share of dead migrants at sea on the Western route grew remarkably, as the following chart shows.

The above bar chart shows the share of migration victims by migration route. In 2014, almost none died following the Western route: as migration policies changed between Italy and Lybia, some migrants tried their luck trying to land on the Spanish coast. Data about 2021 show that, so far, the situation from 2019 is, now, stable.

Unfortunately, we know little about the conditions of migrants in North Africa. Reports talk about lager-like conditions, with systemic violence, torture and rapes being denounced by a number of NGOs, including Amnesty International. Yet, the next chart can offer some insights.

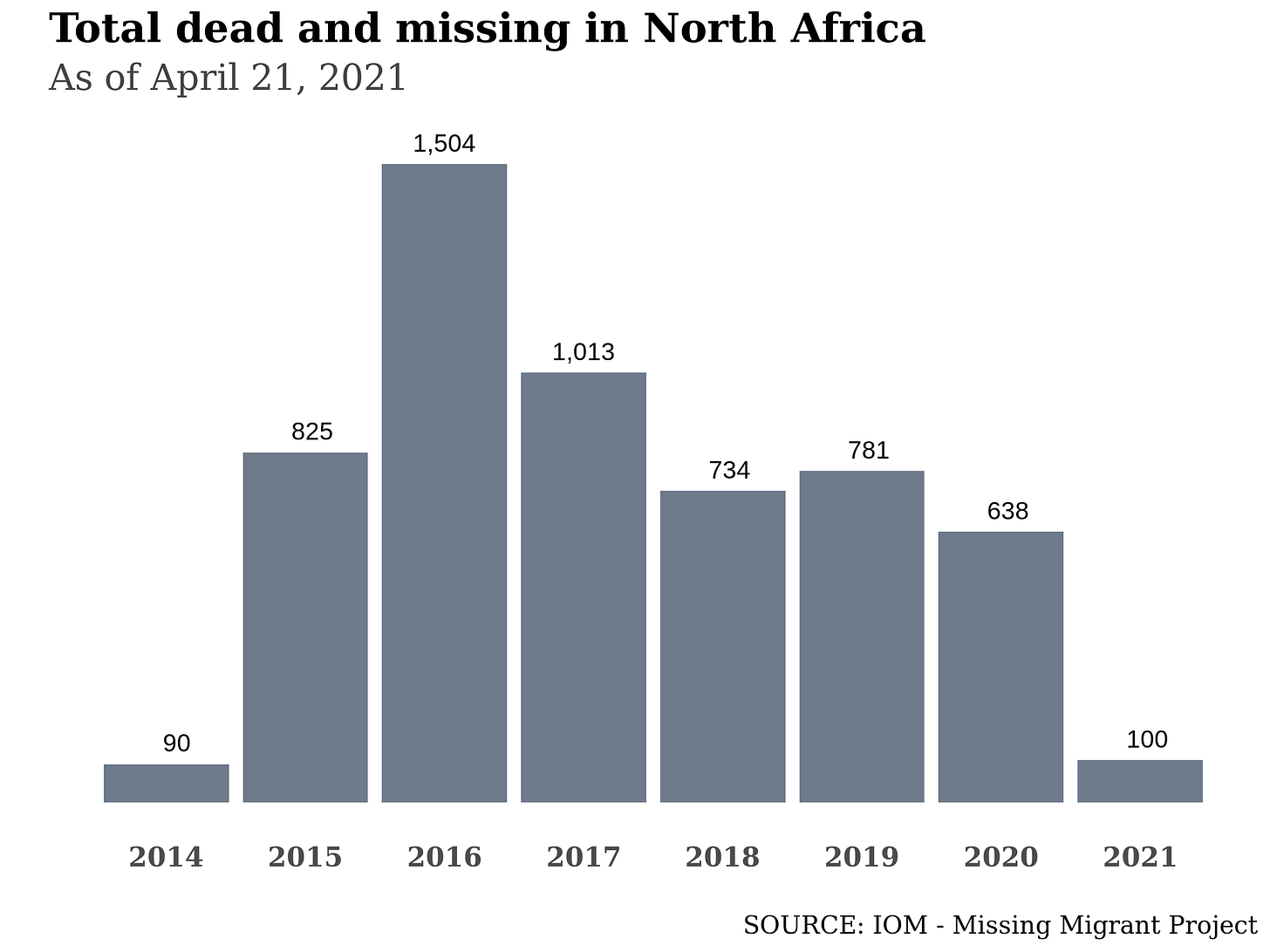

With the assumption that travelling by land is inherently less dangerous than travelling by sea, the above chart shows a very grim perspective for those who think that the problem is within the Mediterranean Sea. The number of dead and missing people grew between 2018 and 2019 and, despite a slight decline in 2020, the number for 2021 was already 100 as of April 21, 2021.

The problem of migration in the Mediterranean looks insolvable. Italian former prime minister, Enrico Letta, advocated for a series of UN-managed humanitarian corridors, but the proposal didn’t find strong supporters so far. The debate on migration on Italian media is fading away until the next tragedy will require an update of these maps.

amazing

Well done!