Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Democracy * But Were Afraid to Ask

A data-driven dive into the *mythical* relationship between democracy and development

Dear reader,

It has been a while… I decided to change the frequency of this newsletter and to run it monthly. I decided so because I make everything on my own. And, if I want to maintain a good level, I need to have some space between one issue and the other. I hope you do not mind.

Today I write you about a subject I care about a lot: why is democracy in crisis? A few highly experimental charts will answer. (Feedback is welcome!)

BRUSSELS — For more the 60 years, we lived under the assumption that democracy was the magic wand capable of bringing welfare and stability to the countries where it flourished. This assumption is increasingly hard to prove, particularly in 2021, in the last phases of a pandemic and where a large part of the world had been experiencing democratic declines for more than a decade.

Is it time, already, to sing the Requiem mass for democracy or we are asking ourselves the wrong questions? Before moving on: what do we mean by ‘wrong questions?’ The following chart will answer.

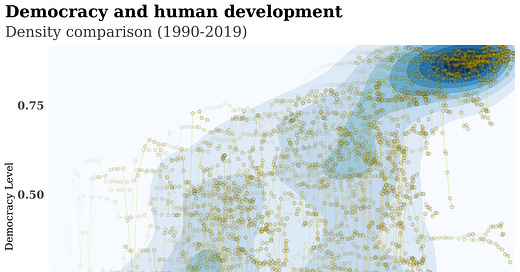

What looks like something between a data visualization and a work of contemporary art shows, on the horizontal axis, the level of human development (HDI) and, on the vertical axis, the level of democracy. The golden lines and points represent the trajectory of individual countries between 1990 and 2019. More recent data appear with a darker shade. The spots in the background show where countries are more likely to be concentrated.

The big blue spot on the top-right corner represents everything we were told about democracy since WWII: that stain is the Western World: U.S. Europe, most of South America, a little of Asia and Africa plus Australia and New Zealand.

If we, superficially, read this chart, we see that the majority of highly developed countries are democracies. There is a very small number of authoritarian regimes with a very high level of human development: they are very few and they are localized in precise areas of the world like the Persian Gulf. A simplified version of the chart above will give us a better grasp of reality.

HDI is an indicator developed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and it pools together other indicators like GDP per capita, education, child mortality…. The indicator for democracy used here is V-Dem’s Polyarchy which measures how (on a scale from 0 to 1) a country fulfils the ideal of democracy. The square at the top-right corner of the chart is (more or less) the position of the first chart’s dark blue stain.

The names of individual countries are not important here. What we see is that the world is getting more developed. The mass of points move rightwards, but the real news is that countries are extremely segregated when it comes to democracy.

Also, the above chart shows that democratic regimes reached their developmental peak. Once they reach the humanely maximum possible level of HDI, they no longer move rightwards. Those once called developing countries are improving, moving towards higher levels of development. The consequence is that the gap between highly developed and developing countries is narrowing. This is confirmed by the following chart.

Here, we see that the difference between the most developed country and the least developed one is getting smaller every year: it was 0.563 in 2019, it was 0.651 in 1990. This change is enough to enable critics of democracy to say that democratic regimes lost their propulsive force. Are they right? Let us take a look at what is happening in one of the strongholds of Western democracy: the European Union.

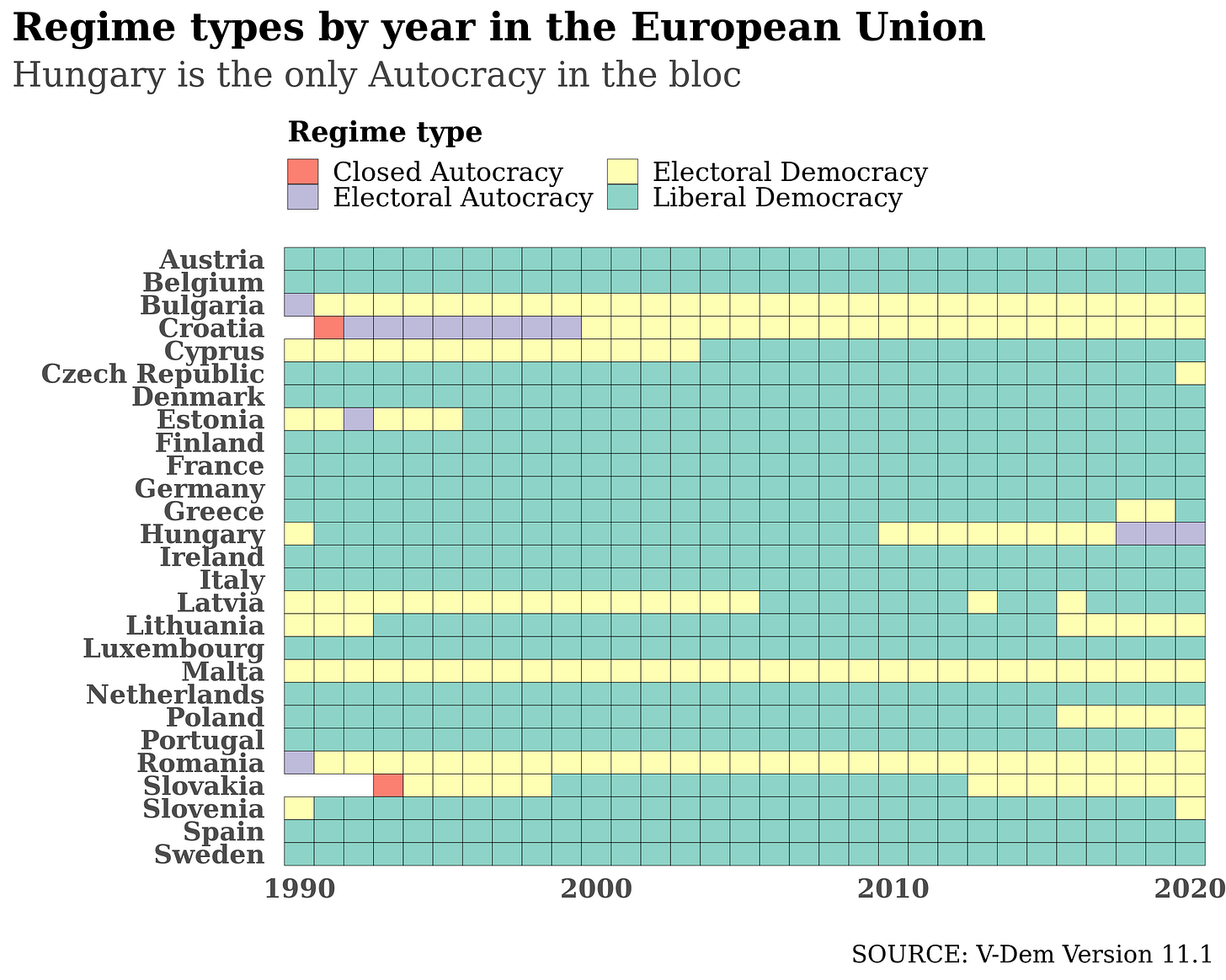

In the chart above, DaNumbers puts in evidence a selection of countries that experience severe issues with their democracy. Those countries were part of the Eastern bloc during the Cold War. Now, they are part of the EU, but they do not seem to be happy with democracy. In fact, since 2018 the EU is home to a non-democratic country: Viktor Orban’s Hungary.

The chart above pools together the regime classification by the V-Dem dataset. After a complicated measurement mechanism, V-Dem scholars categorize countries by their regime type. Only Greece improved its level of democracy in 2020. Many countries deteriorated it and some EU member states passed from a full democracy (Liberal Democracy) to a damaged democracy (Electoral Democracy).

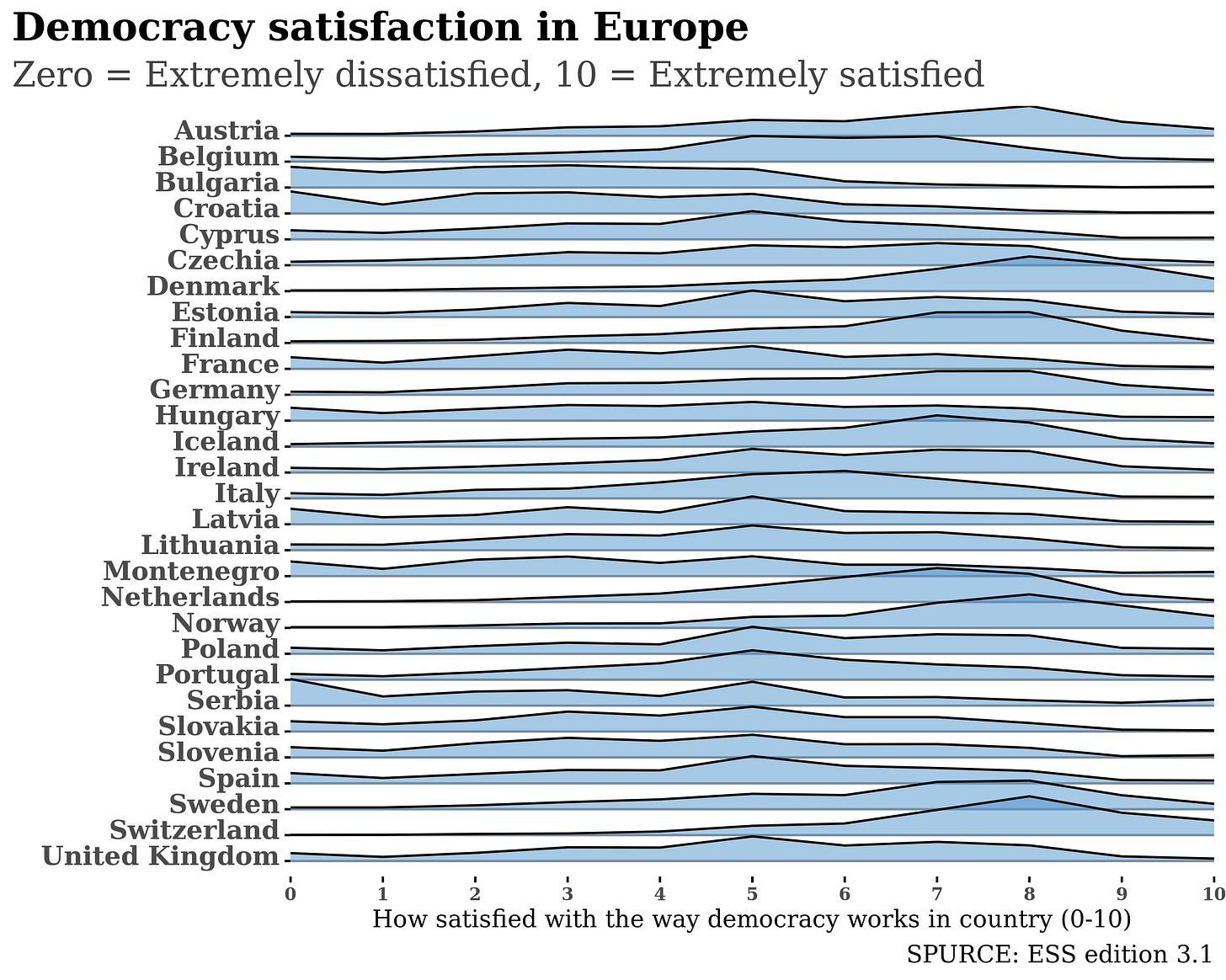

The real problem, though, is that the democratic backslidings are not so difficult to understand if we ask people if they are happy with democracy as such. And, in this case, there are even more uncomfortable questions to be asked. The real issue is that people (at least in Europe) do not appear to be satisfied by how democracy works, as the following chart will show.

If European citizens were satisfied by democracy, the curves of the above chart would be very high on the right-hand side of the ridges. They are not. In countries where people satisfied with democracy prevail, they prevail by a small number. Moreover, even in Nordic countries, where democracy is historically more developed, democratic enthusiasts do not represent the majority.

The peaks in the ridge are never above 30 per cent of the respondent, and they are represented by Switzerland’s eight, on a scale of ten.

France, the U.K. and Italy have a plurality of citizens relatively happy with democracy. Contradictory evidence comes from the East. In Bulgaria, Croatia or Slovenia, people are dissatisfied with democracy. Poland and Hungary are even more puzzling. In Hungary there is not a clear tendency: people are not democratic enthusiasts, but the sample collected by the European Social Survey (a vast pan-European public opinion survey) is evenly distributed.

Poland, on the other hand, appears to be relatively happy with its system. The data are indeed from 2018 (hence before COVID and, more importantly, the abortion issues of late 2020), but the fact that a democratic country is happy with its damaged regime partially demonstrate that there are massive problems with democracy. Among them, the fact that the development/democracy relation is just too easy to be true.

Maybe, what we have been witnessing in the last decade was not only a democratic backslide but an existential crisis of democracy as a theoretical construct. Who needs democracy, after all, if one can buy a house, have a decent job and afford a holiday in Croatia? Moreover, there is an increasingly big body of scholarly literature arguing that autocratic regimes can produce development, in terms of healthcare, wealth, education, etcetera.

So, who needs democracy? Maybe, it is not a question of need but a question of want. The theory that democracy and development work hand-by-hand and feed each other’s is a religious dogma, rather than an actual theory.

If the West is genuinely concerned about the future of democracy, it should stop searching for a rational argument for it and take representative democracy for what it is: a political system based upon faith in its sacred values of freedom and equality. This argument is uncomfortable, given the data-driven societies we live in, but maybe it is the missing leap to explain why democracy is in crisis, as an ideal rather than an indicator.

Is democracy lost forever? No. Maybe, the rise of powers like China and Russia will force the Western world to reframe its narrative and to build a better doctrine to defend democracy, but all of this is just speculation. Maybe, in a few years, more data will emerge and will prove this analysis wrong. In the meanwhile, let's just hope that democracy doesn't deteriorate further: I don't want to submit this newsletter for censorship before I send it out.

Here is the code I used for this newsletter, there is also a premium chart hidden somewhere.

Thanks for reading, see you soon.

CORRECTION: In a previous version this article stated that the Polish abortion issues were in late 2019, they happened in 2020.