Dear Mr. Putin, what do you want?

Data about Eastern European countries show the real aim of Russian foreign policy -- and what is wrong with that.

Dear readers,

this monthly newsletter couldn’t be about anything else: this month, DaNumbers tried to understand the foreign policy of Vladimir Putin starting from a Russia Today OpEd and finishing with one of the best readings by Anne Appelbaum in years. In the middle, you can find charts, and numbers about the context of a crisis which is casting a dark shadow over the entire world.

BRUSSELS -- Russia Today, the semi-official English-speaking channel of the Kremlin, published, on its website, a significant and creepy analysis by one of Russia's top thinkers, Sergey Karaganov, honorary chairman of Russia's Council on Foreign and Defense Policy. The article boldly states that Russian foreign policy must give Russia the role of leadership for the world.

After five centuries of leadership, Professor Karaganov says, the West lost its moral guidance and economic brilliance, even though the EU – the largest free trade area in the world – grew between 1.8 and 2.8 percent in the five years before the pandemic. Furthermore, do these Russian theories have any base? The following chart will show.

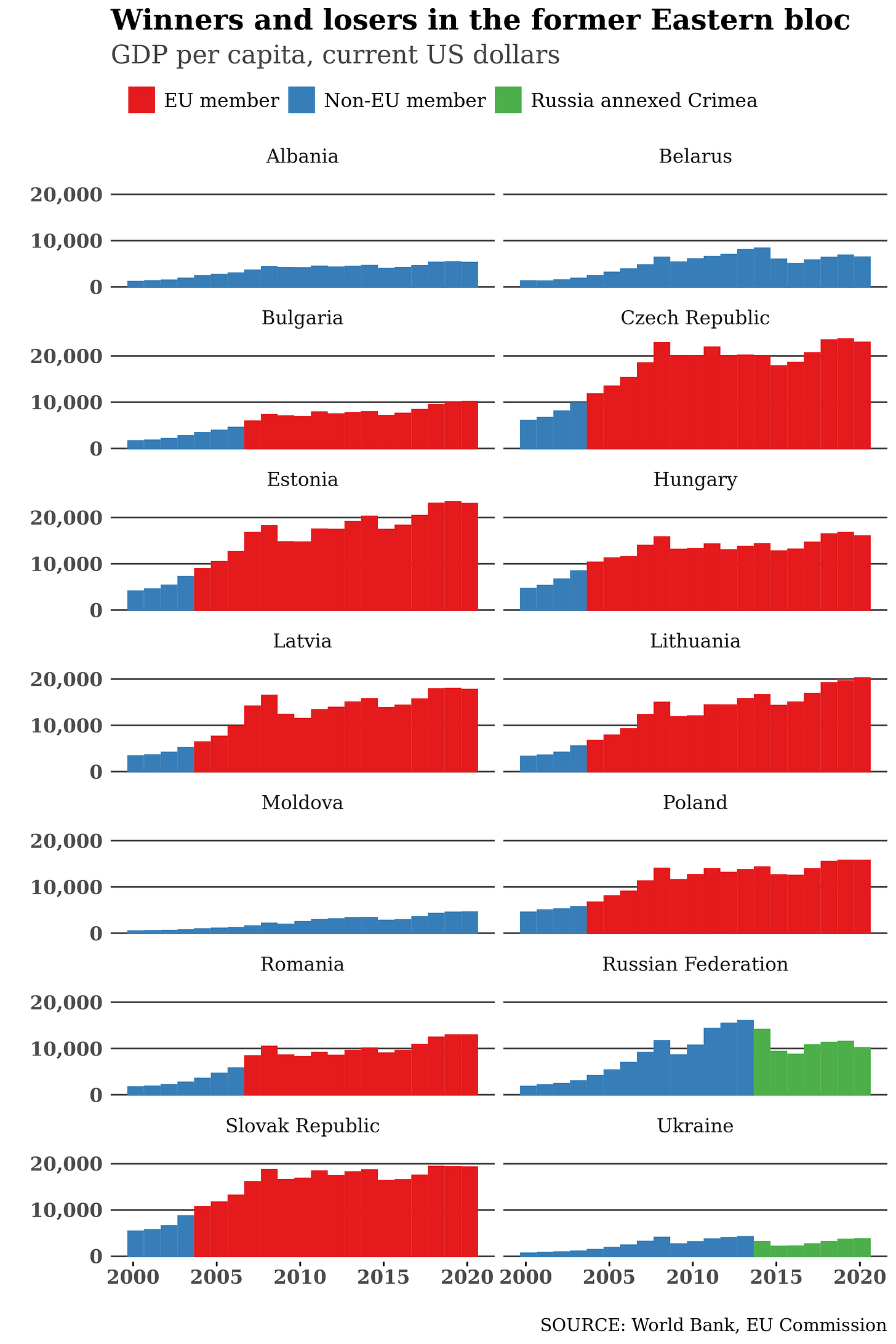

The above chart shows the GDP per capita (current U.S. dollars) for all the original Warsaw Pact member states, including former parts of the Soviet Union like the Baltics and Ukraine. The choice is pertinent because nine out of 14 states are now members of the European Union and NATO. This selection allows us to measure the benefit of EU membership relative to a control group. The control group comprises Moldova, Albania, Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia.

The easiest way to look at the chart is to assess the success of countries from the former Warsaw pact when they joined the European Union. They all saw their GDP per capita (a decent proxy to understand the wealth of a country) grow after they joined the EU. The biggest success stories are, in this aspect, the Baltic republics.

Estonia became the richest country among them, with a GDP per capita of around $20,000. The Czech Republic follows. Poland, for instance, can be used as a reference for what Ukraine could be, should Kyiv survive and the EU in the future. Also, the chart shows the dent caused by Western sanctions on Russia after 2014: according to World Bank data, the average Russian, in 2020, was poorer than a mean Romanian.

In general, non-EU countries lag. Only Russia's GDP per capita is consistently above $10,000, with Moldova, Albania, Belarus, and Ukraine way below that threshold. Russia, according to the chart, is an outlier: it managed alright even without the EU, and this is, perhaps, why Putin thinks he can win the confrontation he is engaged in and, possibly, impose an economic model to be as rich as the Eastern part of the EU. Would that be enough to say that he has a point?

Russia Today recently aired a documentary about the recklessness of the Ukrainian leadership since the country gained independence. The documentary insisted a lot on the flaws of Kyiv's economy. Yet, Russia has its weakness, as the following chart will show.

The previous chart shows the dependence of Russia on natural resources. It includes everything: oil, methane gas, titanium, and others. In the former Eastern bloc, the Russian Federation is the only country to depend so much on natural resources. In countries rich in coal like Poland, natural resource rents amount to 0.7 percent of the GDP. In Ukraine, they amount to 1.8 percent.

The fact that countries not yet in the EU have relatively bigger resource rents is maybe a causality. Yet, the above chart compounds the common perception of Russia as a resource powerhouse. Depending so much on natural resources, Russia should be particularly vulnerable to Western sanctions. Russia, after all, is the second methane gas producer in the world (705 billion cubic meters, the U.S. produced 960 in 2020), and European countries could choose alternative suppliers had they enough political will. The problem is that Russia can count on a very loyal clientele, as the following chart shows.

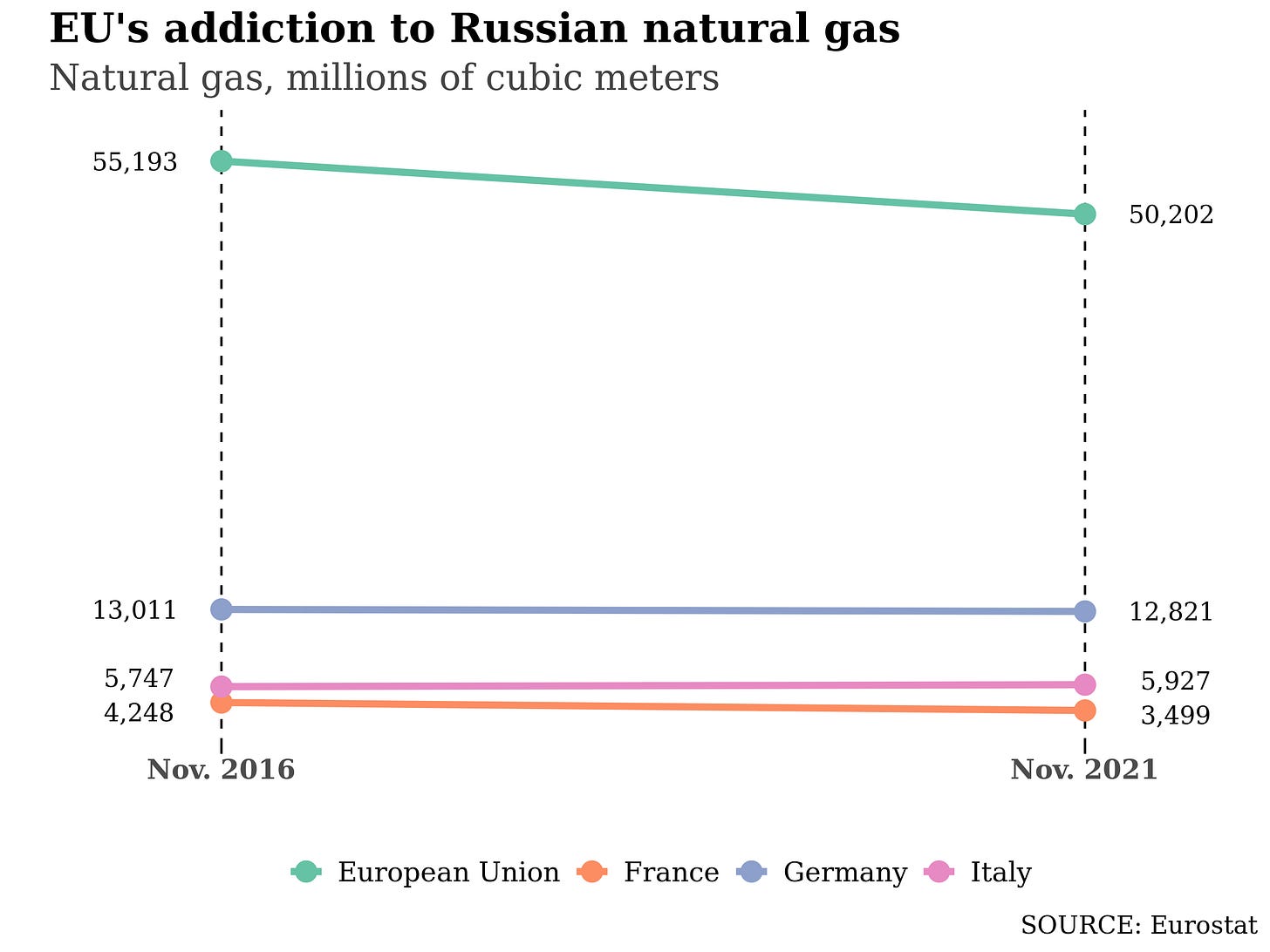

Here DaNumbers compared Russian exports to the EU in its current configuration in November 2016 and November 2021. The EU imported circa 10 percent less methane gas from Russia (minus 5 billion cubic meters). But the unsettling part is that the three largest EU economies (Germany, France, Italy) kept their import constant. Germany kept the level of its import at around 13 billion cubic meters of gas, for example. Data show how Vladimir Putin can count on a continuous stream of Euros to fuel his economy.

Can the Russian president use these Euros to build an alternative model to Western-style democracy? Here, things can be trickier, as the following charts will show.

Here DaNumbers tries to predict a change in GDP per capita according to how much economies rely on natural resource exploitation over the decade between 2010 and 2020. Statistically, the regression is significant (p-value = 0.00001), but the model explains only 10 percent of the position of the points in the chart. Theoretically, a 1 percent point increase in resource rents translates into a 1.4 percent point decline in GDP per capita change.

The results do not prove any relation between resource rents and GDP. The same applies to the link between change and absolute GDP per capita. Although not exhaustive, data show that, if anything, each country has its own history, its own political regime, and its own model of society. What does it mean? The following chart will say.

The chart above tries to correlate regimes and growth against the level of democracy. Results here are inconclusive (p-value = 0.75). Speaking of Russia, Vladimir Putin's leadership should be in question, given how much GDP per capita declined in 10 years (minus five percent).

So far, data show that Russia has very little to offer, economically, to those following its way despite claims by the Russian Intelligentsia. The real problem, though, is elsewhere. 'Democracy at dusk?' asked the first V-Dem annual report in 2017. Is democracy ‘at dusk’ in Eastern Europe? The following data will answer.

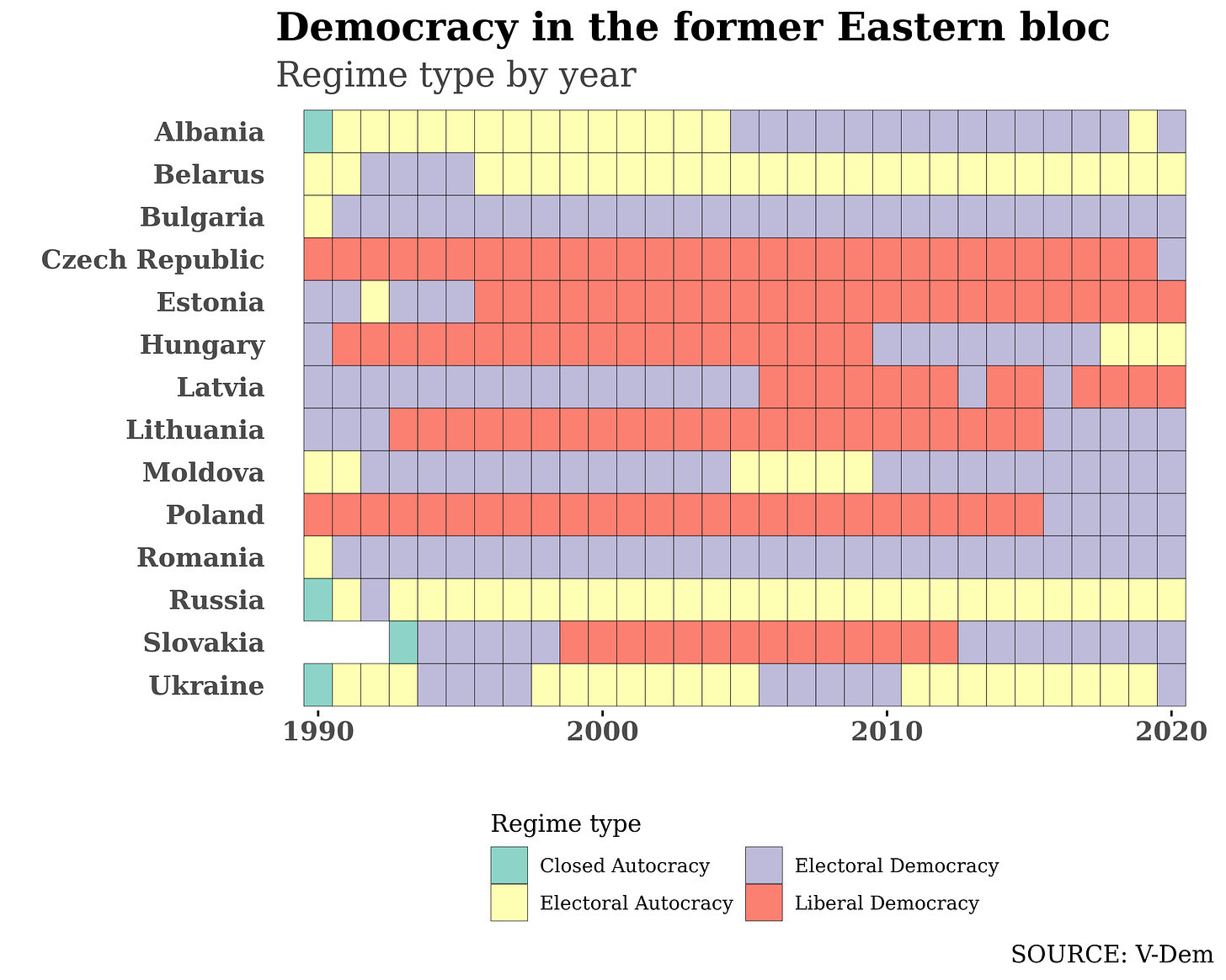

The chart shows the regime type of the 14 countries examined in the first chart. On one side, the chart appears to prove the Russian claims about a corrupt and declined democracy: Hungary stopped being one, and there have been issues in Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, and others.

Yet, despite a democratic backsliding unanimously denounced by research centers worldwide (the last being the Economist days ago), Ukraine became a democracy in 2020. On the other hand, Belarus remained more aligned to Russia in terms of regime type. Finally, Moldova managed to quit an autocratic government in 2009.

Speaking of Ukraine, the swing between regime types denounces Kyiv's fragile and incomplete democracy. Moreover, the regime swings coincide with unrest in the country. For example, Ukraine became a democracy in 2005 (after the Orange Revolution) and an autocracy until the current president Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Here is a link to a methodology document for more information about how the V-Dem Institute, DaNumbers’ data source, computes the regime types.

The bottom line here is that, despite the Hungarian case, the integration of Eastern Europe into the Western system of relations proved to be a success. Even Albania, once of the most ferocious regimes in the Warsaw pact, looks now well into a democratization process. Albania has been part of NATO since 2009.

As Anne Appelbaum wrote recently, western-style democratization and development are Putin's enemy. She suggests (with other authors) that if Russians realized what Putin is really about, his regime would instantly enter a legitimacy crisis.

Moreover, Ukraine is not just another country, under the Russian perspective. For them, it is where Russian history started. A successful breakaway of Kyiv would put Russia's self-proclaimed leadership of the Slavic world in jeopardy. Something the current Russian tzar (ahem, president) can't afford.

Click here to read the code used for this newsletter.

I really like your work! Looking forward to reading more articles in the future.