Data vs. bookmakers: who will win Eurovision 2024?

A data-driven analysis of the songs predicts unlikely winners for the 2024 edition. Did DaNumbers spot some underrated dark horses?

Dear readers,

This is the first episode since the departure of my friend and mentor, Roberto Reale. He was a pillar of the Italian digital ecosystem and a far-sighted innovator. In this picture, you can see the two of us presenting his last book together in Brussels. There is an infinite number of reasons why I miss him. This episode is for his memory and our friendship.

Thanks for reading.

BRUSSELS – Dark horses or real contenders? This newsletter’s episode plays on the fine line between spotting the real winner and identifying potentially underrated songs in the most colorful music festival in the World, and bad data science. After the first rehearsal, bookies identified some potential winners. As of May 2, the most likely winners should be Switzerland, Croatia, Italy, Ukraine, and the Netherlands. Although they could be right, DaNumber thinks the top five might look different. According to our methods, the top five will be:

Ronda (Serbia)

Hollow (Latvia)

Grito (Portugal)

ZORRA (Spain)

SAND (Denmark)

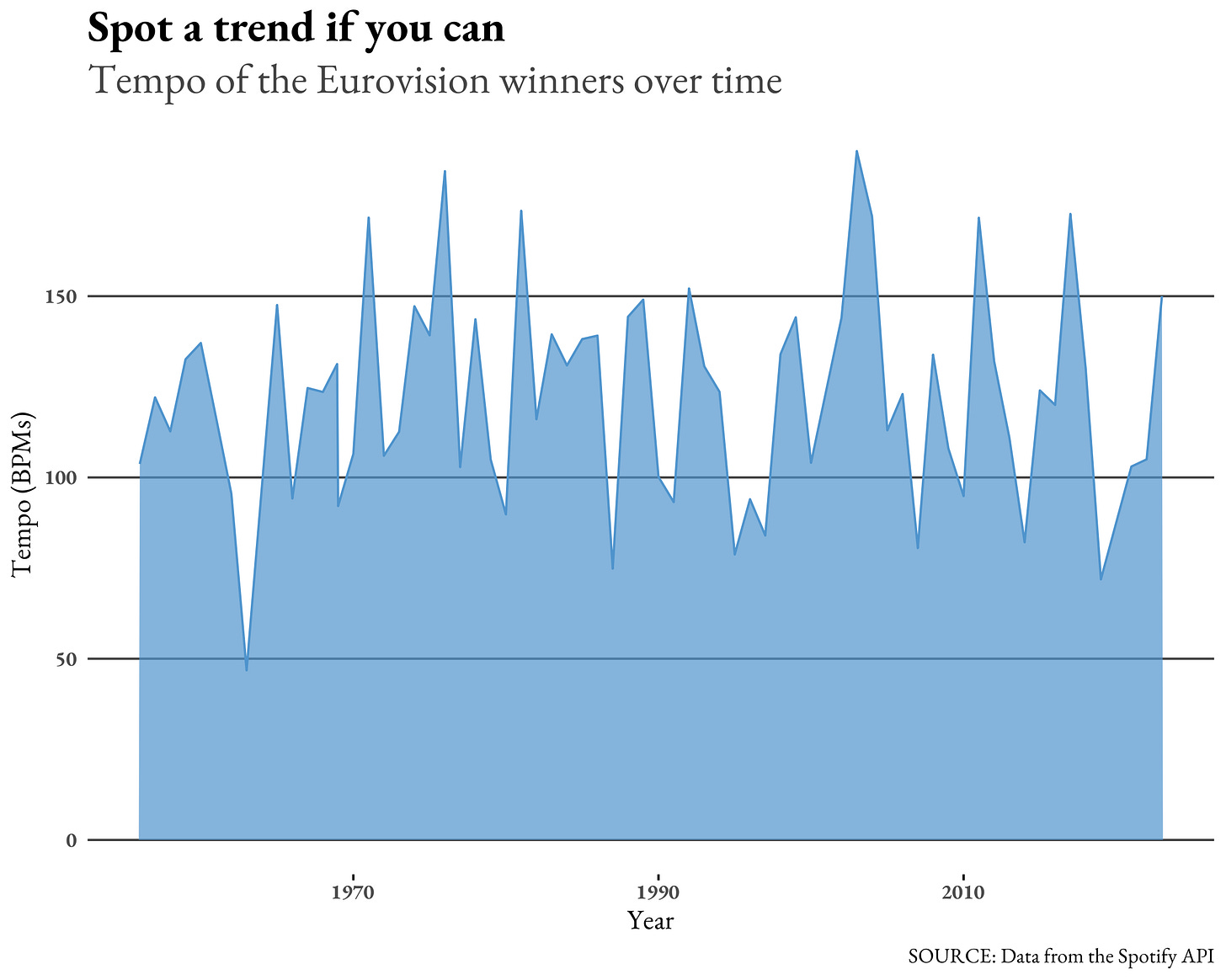

How did we get there? Music, per se, does not explain the results of the contest. Trying to predict the 2023 edition, DaNumbers stumbled upon the roadblock that training a model to predict the chances of a song winning the Eurovision is a pointless exercise. The variables at play are just too many and, often, include the visual appearance of the performers, the politics behind the voting system, and a diversity of songs which is very hard to summarize using data only. The following chart will give an idea.

Here, we see the tempo of the songs that won the Eurovision from 1956. We notice that songs had a tempo between 50 and 150 beats per second, irrespective of their decade. Yet, the crisscross of the songs might offer some element of predictability. What if it was possible to find a trend and, inductively, try to use past trends to understand what the 2024 winning song could look like? This question is where things become complex.

Spotify offers 12 different variables to measure music. Some of them are even dummy variables. Other variables like valence or danceability come from a proprietary algorithm Spotify acquired a few years ago. This is not the first time DaNumbers has used the Spotify API for musical analysis, and, for reference, my last article for Wired Italy used similar techniques to explain the success of the 2021 Eurovision winners, The Måneskin.

This time, we used a Principal Component Analysis to reduce the number of dimensions of the dataset while highlighting information about the songs that won the Eurovision from 1956. More from the following chart.

Here we see the evolution of the two principal components over time. According to these charts, there are some macro trends. For example, rarely, a song similar to the winning song from the previous year wins. This means that, at least in theory, it is possible to predict a Eurovision-winning song because it could follow the pattern of the other Eurovision editions.

This is a very bold statement. A Eurovision victory depends on a lot of factors: the relationships between broadcasters, the fashion of the moment, and the performance by the artists. Bookmakers have their way of predicting the winners (usually being pretty good at it), but the purpose of this exercise is slightly different. Here, we want to understand, if music matters, who is the most likely winner. The following chart leads to some indication of where to look at.

Here, we see the results of an autoregressive model called ARIMA that tries to predict data points in a time series using the trends from the previous points. In this case, we notice that the likely winning song will be a bit boring: little melody, little dance potential. The standard deviation (the line with whiskers on the prediction side), though, raises some questions. The winner might be anywhere, and, as far as we know now, we could see a winner like none in the past 67 editions of the contest. Is this the case? The following chart will answer.

Here, we see all the winners by dance and melody potential within the ellipse representing the standard deviation (where the winning song is likely to be). Within the standard deviation, we see 14 songs. Of them, only three there are from the last ten years: Rise Like a Phoenix (2014), 1944 (2016), and Arcade (2019). The rest belongs to the ‘60s (six songs) with the rest distributed more or less equally among the other decades.

The data so far show that the potential Eurovision-winning song is less exciting than some imagine. The hard part is to find out who will be this year. To do so, DaNumbers filtered the original dataset with the winners within the red ellipse from the previous chart, built a dataset with the 2024 participant song, and performed a new Principal Component Analysis.

Once we identified three components, we averaged their values for the song that won Eurovision in the past and measured how far each song from 2024 was. To be extra precise, we weighted the distance per principal component. Principal components are not all created equal and contribute differently in explaining how variables behave. The following chart will show it better.

On the y-axis, we have the components. Given that we used them as a classification tool (more or less), we decided not to name them. RC1 is the most important because it explains 55 percent of what we see. RC2 is at 24, and RC3 explains 21 percent of the dataset. The percentages are the weights DaNumbers used to average the distance of each song from the ideal-typical 2024 winner. The results of this exercise are in the following chart. The distance was normalized between zero and one.

The above data visualization shows why the prediction is likely wrong: music and data are not the only independent variables about Eurovision winners. Also, the songs seem homogeneous, aggregating around the red dot (the average distance from our unknown winner). The last sentence means that this kind of deterministic analysis might be interesting for a newsletter episode but could also be a giant load of BS.